Hurricane Andrew caused close to $100 million dollars in property damage in the Miami-Dade County school district alone. Roofs were gone, books were soaked, whole schools had to be leveled and rebuilt. But, says Michael Fox, Director of Risk Management for the district, the damage was almost completely covered. “Whatever was not insured, we received grants from the Department of Education to supplement whatever the loss was.”

ANDREW AND WILMA

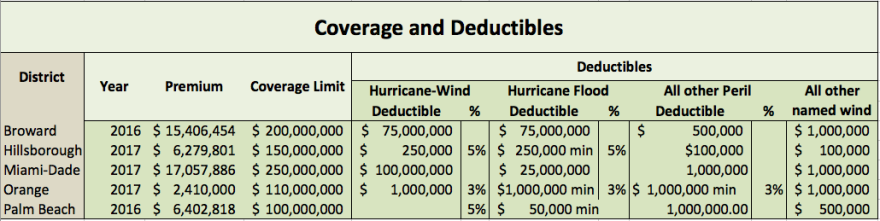

Andrew changed the insurance market worldwide. “At that point, the rates became so untenable that we raised our deductibles,” Fox says. "Currently they’re $100,000,000, and we rely heavily on FEMA to lend assistance in the event that there’s a large-scale hurricane loss.”

“I think the real effect to the market, in South Florida especially, was 2004-2005 when we had three storms in 18 months,” says Linda King, Risk and Safety Manager for Palm Beach County Schools. At the time, she worked in Martin County, with a pool of school districts that shared $200 million dollars in property insurance.

“The first renewal after Hurricane Wilma, a lot of us had terms that said after you have one storm, we’re going to reinstate your deductible, and make you satisfy it for a second storm,” King laughs. “And by the way, we’re going to charge you more and give you less coverage.”

Some insurance companies pulled out of Florida altogether after Hurricane Andrew. The state’s building codes got much tighter. And as insurers tried to get better data on the risks they were taking on, they turned to computer modeling, demanding more and more granular information from their customers.

LAYERS OF TRANSACTIONS

“The computer models will just pull in your school like a house of sticks unless you tell them this is the type of concrete I’m using, this is the type of roof I have,” King says. Buying insurance for a system as big as a school district in Florida is complicated. Not one company is going to take on 100% of the risk—or even 50% or 25%—so you can’t just shop around for the best deal.

As a result, most large entities like school districts hire a broker as a middleman.

“They’ll say, we’re looking for someone who can provide the service of going out to the marketplace, and negotiate with all the insurance carriers,” says Don Dresback, Executive Vice President at Beacon Group, in Boca Raton, the broker for Palm Beach school district.

"When you’re talking about billions of dollars in assets," he says, "your broker might hire another broker, who hires another broker, so that the risk is sliced up in markets all over the world."

Gary Reshefsky, a risk management consultant who serves on an insurance advisory board for the City of Coral Gables, says these arrangements can make it hard to see exactly what you’re paying for.

“In a lot of cases, the broker is paid a percentage of the premium as their commission,” says Reshefsky. The other brokers they hire might get a percentage commission on top of that, sometimes with brokers at each layer of transactions all owned by the same parent company.

Reshefsky worries paying brokers a percentage instead of a flat fee sets up the wrong incentives. “In a year where the premium goes up, their commission goes up, and in a year where the premium goes down, their commission goes down,” he says.

Districts tend to work with the same broker in multi-year contracts. Only one of Florida’s five largest districts —Palm Beach— has changed brokers since 2010. School districts want stability, so the broker understands enough about their property portfolio to get them good rates, and so they can lean on that longstanding relationship when the insurance market gets tight after a storm.

On the other hand, with a three or five year contract, Reshefsky says, “You’re putting your broker on notice that they’re going to keep your business next year no matter what.” The actual placement of insurance, he says “is happening outside of any kind of transparency as to what went into the ratemaking.”

MORE SAVINGS TO BE HAD?

Commercial insurance rates have dropped across Florida after a decade without a major storm, and Reshefsky believes public agencies could do a better job capturing the same savings as private companies. “Without competition,” he says, “you as a public entity are not going to drive the best terms and conditions.”

The amount districts pay their brokers varies widely, even when you factor in the size of the policy or the level of deductible. For example, Orange County Public Schools pays its broker a flat fee of $85,000 a year. Miami-Dade County Public Schools have twice as much property to cover—$10.1 billion in assets—in a higher risk area, but paid more than 20 times as much as Orange County in commissions last year, well over $2 million.

Both Miami-Dade and Broward stayed with brokerage company Arthur J Gallagher the last time they renewed their contracts, despite the fact that Gallagher’s fees were higher than competitors.’ The district’s chief financial officer, Judith Marte, explained her reasoning at a meeting during the procurement process in September 2015: “My concern is short-term savings versus long-term stability,” she said.

Don Dresback, the broker for Palm Beach County Schools, had put together an competing offer for Miami-Dade that included roughly a million dollars less in commissions each year than what the district paid Gallagher. But Marte’s primary concern, she explained, was the fear the district wouldn’t be able to buy enough insurance after a storm. Arthur J Gallagher has been the district’s broker for more than 20 years, providing full-time support staff that work out of MDCPS offices. “When there is a catastrophe, and the market tightens, I believe that [relationship] is going to matter a great deal,” Marte said.

But there was one other consideration too. “Scott’s retirement has gotta be part of the equation,” she said. Scott Clark, an insurance manager who spent 30 years at the school district, had retired just a couple months earlier, in June. In September, the district opted to stay with the same broker, and the following month, the broker gave Scott Clark a new job. He became Gallagher’s Area Vice President.