There’s an old saying among Mexican officials when dealing with the United States: Always tell the gringos yes, but never tell them when.

That dance is the result of two centuries of tortured bilateral relations marked by U.S. insensitivity and Mexican hypersensitivity. And it’s most likely what’s playing out now as Washington and Mexico City haggle over the fate of a former U.S. Marine, Andrew Tahmooressi.

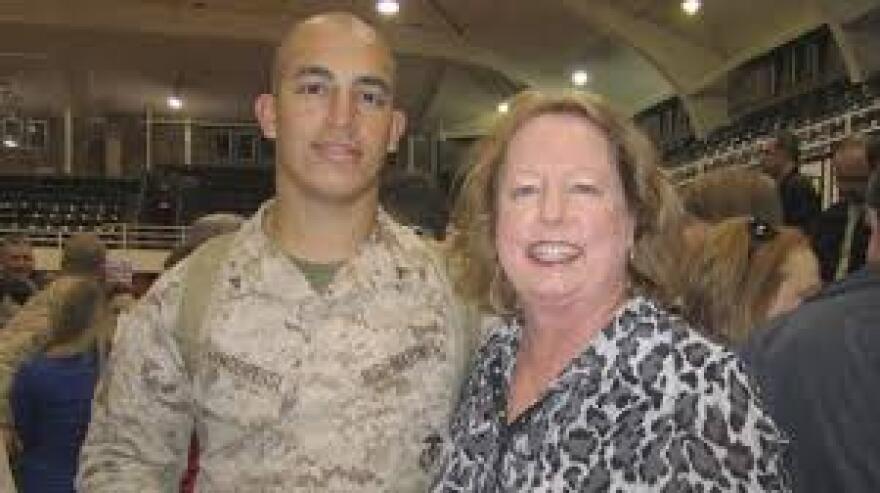

Tahmooressi is a South Florida native who served two tours of duty in Afghanistan and suffers from post-traumatic stress disorder. In March he says he mistakenly drove his pickup – with legally purchased guns inside – from California across the border into Mexico, where civilian gun possession is illegal. He was arrested, and he says he’s been subjected to violent abuse in a Tijuana prison as he awaits trial.

RELATED: Jailing of Florida's Aqua Quest Crew Raises Honduran Justice Issues

His case is getting more attention now because of the negotiated release of Army Sgt. Bowe Bergdahl, who until last weekend had been a prisoner of the Taliban in Afghanistan for the past five years.

Bergdahl was swapped for five Taliban militants being held in the U.S. base prison at Guantánamo, Cuba. As a result, a rising chorus of Americans is now asking: If we could extract Bergdahl from the Taliban, can’t we surely spring Tahmooressi from the Mexicans?

The answer is probably yes… we just don’t know when.

In other words, it’s not that simple.

In Latin America, an often justified resentment toward Washington – but also serious judicial dysfunction and corruption – can obstruct the kind of resolutions we expect.

Especially in Latin America, where a long history of often justified resentment toward Washington – and also a long history of judicial dysfunction and corruption – can obstruct the kind of resolutions we too often take for granted in cable-news-cycle America.

It’s what may prolong Tahmooressi’s release – and it’s a factor in a growing number of other legally controversial cases of yanquis locked up in Latin America these days.

Among them: Alan Gross, the 64-year-old U.S. aid contractor serving 15 years in a Cuban prison on questionable espionage charges after he brought illegal satellite communications equipment to the communist island in 2009. And more recently, six crew members of a Florida-based ship, the Aqua Quest, who were jailed a month ago in Honduras for having guns onboard that they insist they registered with authorities.

Bergdahl’s liberation has raised perhaps unrealistic expectations about their freedom, despite the flimsy nature of their prosecutions.

“We often think these things occur in a vacuum, that if you did it there you can do it here,” says Frank Mora, who directs Florida International University’s Latin America and Caribbean Center and was Deputy Assistant Secretary of Defense for the Western Hemisphere.

“But in each case you have to account for the normal play of politics and competing interests. In Mexico, the thing to remember is its sensitivity regarding Americans carrying weapons inside Mexican territory.”

There’s also the issue of U.S. guns being smuggled across the border, fueling the country’s horrific narco-violence. If anything, Tahmooressi’s wrong turn south – with a shotgun, rifle and handgun in his vehicle – gives Mexican officials an opportunity to showcase their anger over Washington’s chronic refusal to ban the assault weapons that so often end up in the hands of Mexican drug cartels.

That doesn’t excuse the venality and molasses pace of Mexican justice, not to mention the squalid and brutal prison conditions Tahmooressi is experiencing. But it helps explain why his release could turn out to be a more baroque process than the U.S. hopes.

SPY SWAPS

Unlike Bergdahl’s case, there’s no prisoner swap scenario available for Tahmooressi – just as there most likely isn’t for Gross, even though the prospect is constantly raised in the media.

That’s because Cuban leader Raúl Castro is holding Gross in large part as payback for the so-called Cuban Five – now the Cuban Three since two of them have finished their sentences and returned to Cuba – who were convicted in the U.S. a decade ago as spies. But it would be much harder for President Obama to somehow pardon any of those Cubans and exchange them for Gross, who insists he’s not a spy.

The U.S. does still arrange “spy swaps” with countries like Russia. But Cuba is another matter given the political power of the Cuban exile lobby in the U.S., which sternly opposes any such trade in this case. As a result, says Mora, “Obama is really not prepared to take that measure.”

The trick for the U.S. is to find a bargaining chip it can use to win Gross’ release, such as removing Cuba from the State Department’s list of countries that sponsor terrorism – which most Cuban experts say should have happened years ago anyway.

Mora says he’s optimistic about a quicker release of the Aqua Quest crew. The U.S. wields stronger leverage in Honduras – which desperately needs Washington’s help to stem its own drug-gang nightmare.

That makes it easier to find out not only if a prisoner will be released, but when.

Tim Padgett is WLRN's Americas editor. You can read more of his coverage here.