“The first [B]lack superhero of the modern age.”

That’s how author Sudhir Hazareesingh describes François-Dominique Toussaint Louverture, one of the most important liberation heroes of the Americas. At the end of the 18th century, Toussaint led a remarkable revolution that made Haiti the first republic founded by formerly enslaved Black people — but he's received relatively scant attention from historians.

In these uncertain times, you can rely on WLRN to keep you current on local news and information. Your support is what keeps WLRN strong. Please become a member today. Donate Now. Thank you.

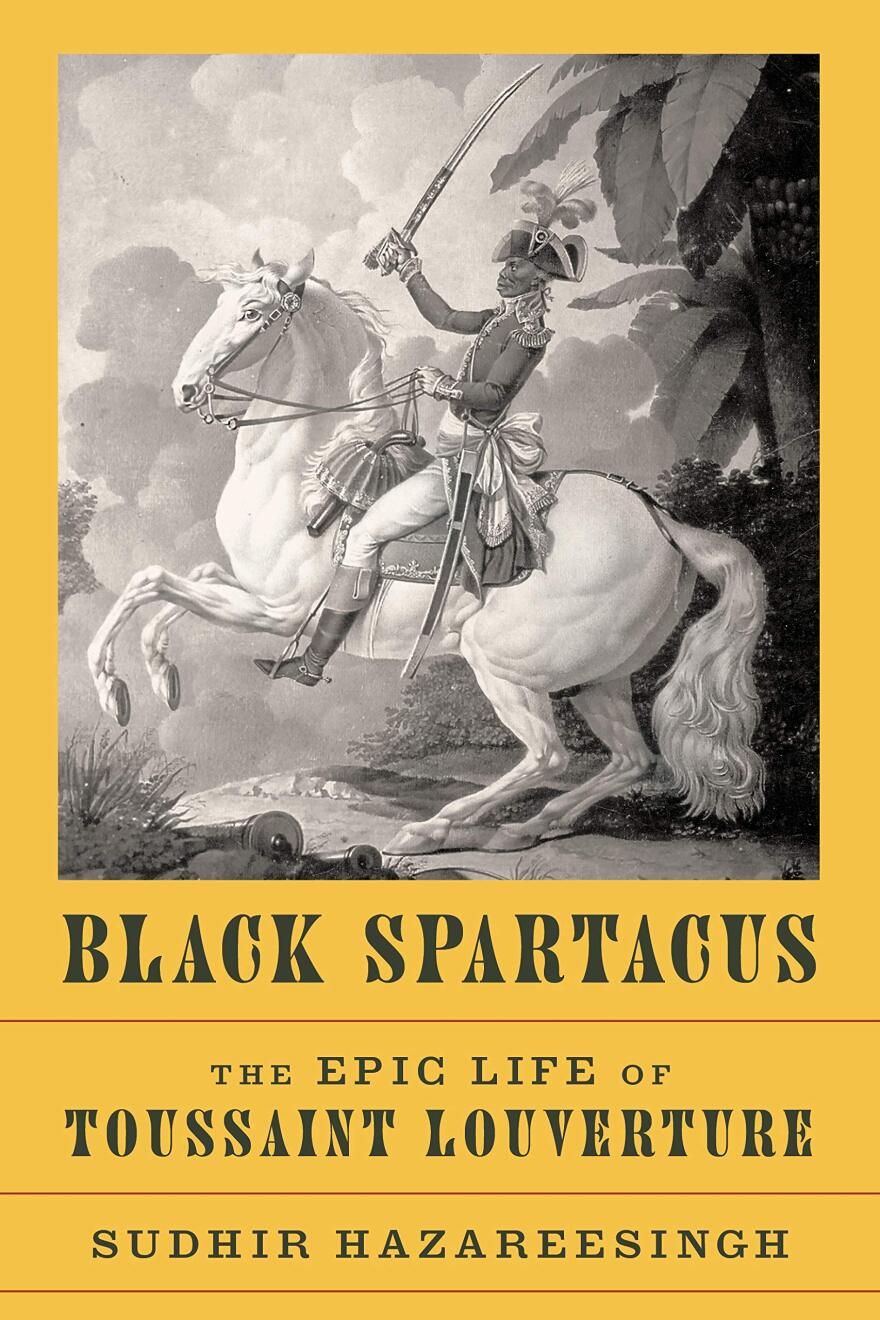

Hazareesingh’s new, richly detailed biography “Black Spartacus: The Epic Life of Toussaint Louverture” should help change that — and confirm how importantly Toussaint and Haiti’s revolt resonate beyond the Caribbean island of Hispaniola.

Hazareesingh, a historian at Oxford University in England, spoke from there with WLRN’s Tim Padgett.

Here are some excerpts from their conversation:

WLRN: So if Toussaint is the first modern Black superhero, then “Louverture” was his superhero name. Tell us how he got it.

HAZAREESINGH: Well, that's a terrific story. In 1793 Toussaint issues a really wonderful, proud, powerful proclamation where he calls himself “L’ouverture”…

Literally meaning “an opening”…

An opening, exactly. So this is thought to be a nod at the Enlightenment — that through learning, people would recognize that slavery was fundamentally unjust. But at the same time, it's a nod to the Vodou religion, because one of the Vodou gods is called Papa Legba, who leads people from one part of their lives across to the other.

READ MORE: Haiti 10 Years After the Earthquake: Why So Little Recovery Progress in a Decade?

What made Toussaint so different from other Haitian revolutionary leaders?

He had exceptional talents. He was a warrior and a philosopher. He was a voracious learner — and a just as voracious writer who, at the height of his power, was dictating some 200 letters a day.

His father had been a senior official in the African kingdom of Allada [in what is today Benin in West Africa]. And his father taught him about the military traditions of its people, the religious traditions and also the scientific traditions.

Of course, 18th-century Saint-Domingue, as Haiti was known, had a very vibrant local culture; and Toussaint absorbed Catholicism, the resistance ideas of runaway slaves and especially the Vodou religion. His capacity to take these influences and mix them with the ideas he received from the European Enlightenment produced something very original and distinctive.

But describe for us just how awful — savage, really — the enslavement of Black Africans was in the French colony of Saint-Domingue, which is now Haiti.

It was a barbaric regime. By the late 18th century, there were half a million enslaved men and women [there]. Slaves were routinely beaten by whipping or with clubs. People could have their limbs cut off, or an ear. Exploding gunpowder was used as bodily torture. And of course, there was a massive amount of sexual violence against women.

Yet there's a striking scene in the book when Toussaint intervenes to stop the execution of white prisoners because he felt it would “reflect poorly on the slave rebellion.”

Yes, he wants to lead his people towards emancipation, but he also wants to create a new political community where everyone — Black, mixed-race or white, including people who had been slave owners — agree to live together on the basis of shared values. And he realizes that people need to reconcile with each other as quickly as possible.

Toussaint was a warrior and a philosopher – and a voracious learner. His capacity to assimilate African, Caribbean and Enlightenment influences produced something very original and distinctive.Sudhir Hazareesingh

Even so, Toussaint was also a man of contradictions. He once owned slaves himself; he could be quite authoritarian — and you write that after freeing Haiti from slavery, he was then at first reluctant to free Haiti from France.

This is a colony that is aspiring to freedom in a world where Black people are still considered to be unequal and inferior. And where all the imperial and colonial powers are trying to exploit Saint-Domingue to their own advantage — including the Americans.

So Toussaint has to navigate through these different pressures. He wants to create a situation where Saint-Domingue enjoys a measure of sovereignty, but without going all the way through to independence. He thought France could actually act as a protector.

CRUCIAL ROLE

Toussaint did eventually lead the independence fight. Napoleon's forces captured him and sent him to prison in France, where he died in 1803. But Toussaint’s army prevailed and Haiti became independent in 1804. In the end, you feel the Haitian revolution is more “original” than other revolutions, especially the American and French Revolutions of that time. Why?

Because the Haitian Revolution is more comprehensive. It's democratic and republican, a war of national liberation, and it incorporates these European, Caribbean and African ideals. And most fundamentally, it has at its heart the principle of racial equality, which is only tentatively addressed by the French Revolution — and of course in the American case, slavery is not abolished at all.

What's really extraordinary is the way in which the Haitian revolution then spreads. In South America, you have Haitian influence in Venezuela. [South American liberation leader] Simón Bolívar was later driven by the same ideals as the Haitian revolutionaries — and indeed, Haiti played a crucial role in propping up Bolívar at a crucial moment when his own fortunes weren't looking particularly good. And you feel that influence later on in Cuba too.

You were born in Mauritius, off Africa, and most of your career has focused on French history. What drew you to Toussaint? The fact that Mauritius itself was once a French colony? Or that the Haitian Revolution was inspired in part by the equality-liberty-fraternity ideals of the French Revolution? Or both?

Both. I mean, one of the very pleasurable things that this book allowed me to do was actually go back to Mauritian history. Mauritius is a French colony at the time of the Haitian Revolution, so there are similar things happening, including revolts by enslaved people.

I think my Mauritian background gave me an understanding of how this kind of multiculturalism works in practice. In Haiti, as you know, Creole is a common, unifying language and the same is true in Mauritius.

In fact, the two Creoles have evolved in largely convergent ways. It’s a particularly wonderful language, especially if you’re trying to convey imagery or wit and humor. And there's a lot of that in Toussaint as well.