As climate change and sea rise increase the risk of flooding across South Florida, water managers are taking steps to beef up a regional 1940s-era flood control system that covers more than 2,000 miles of canals.

In a meeting this month, South Florida Water Management District engineers say work has already started on two massive coastal pump stations expected to be completed by 2026.

“When all of these structures were being planned, the population for South Florida was projected to max out about 2 million. It's kind of rocking about 8 million right now,” said Akin Owosina, the district hydrology chief. “Obviously, many of the structures, especially those along the coastline, are vulnerable to sea-level rise, which wasn't a consideration during their design.”

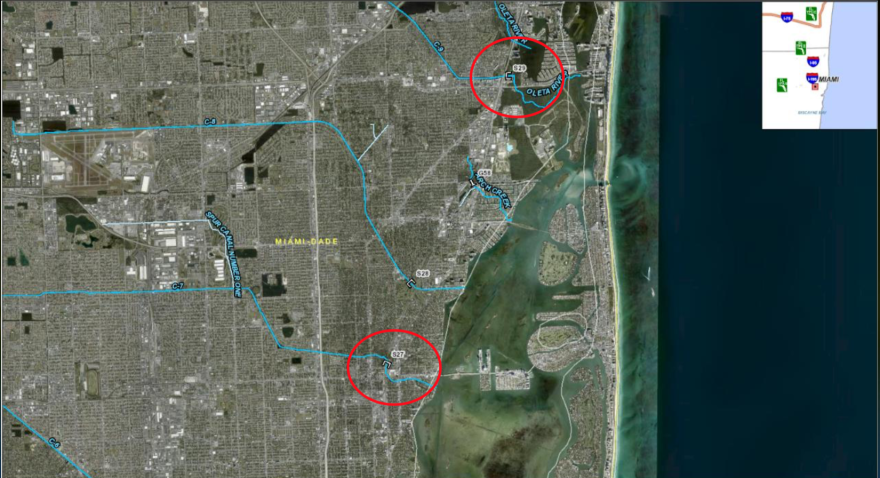

The two pump stations handle flooding in two of South Florida’s most vulnerable neighborhoods, along the Snake Creek Canal at the Broward and Miami-Dade County line, and adjacent the Little River. The resiliency plan is now open for public comment through July 15.

To deal with increased flooding, the stations will be expanded to include additional pumps and generators. They’ll also be elevated to 11 and seven feet.

The district first took a look at the aging system in 2008 and again in 2020 and identified 27 coastal pumps where sea rise would eventually cause them to fail; Owosina said in a presentation this month to give the public a look at the district's draft plan. The district also analyzed land-use changes that gobble up green spaces and wetlands across the 16 counties it manages. All the coastal basins in Miami-Dade and Broward counties ranked at the highest level of priority.

A 2019 Florida International University study has also found that groundwater levels in Broward and Miami-Dade are on average higher during the rainy season, leaving little room for stormwater to drain.

“It does show that even with current conditions, some of those basins are already orange, and we need to actually be able to advance some work,” he said.

The strategy for flood control has also changed, complicating the work, Owosina said. Dumping flood waters that could pollute estuaries and coastal waters and harm manatees, seagrass meadows and other important wildlife and habitat is no longer acceptable.

“Forty, 50 years ago, a good flood protection project sent water to tide as quickly as you could,” he said. “From talking to all of our partners and stakeholders we're working with, that's no longer what they're looking for.”

The two coastal pumps were both installed in the 1950s and will need to be squeezed onto limited land, said construction manager Vijay Mishra, in neighborhoods that have grown up around them and where residents may not be thrilled with the new massive pumps.

“The pumps are going to need a new inflow; they're going to need an outflow, you're going to need generator rooms, control buildings, fuel tanks, all those things are needed. And pumps make noise,” he said.

To keep sea rise from going around, they’ll also need to be tied back to structures on high ground, he said. The pumps will also need to be elevated — 11 feet for the Snake Creek canal pump station and 7 feet at the Little River — although it’s not yet clear elevating the additional structures is possible, Mishra added.

“When we do any of these structure improvements, we are talking about raising the structure itself, raising the gates, our bridges, all the platform, the operating platform, everything has to be raised from where they are by almost nine feet, which is a major challenge,” he said.

At the Little River pump station, he said the work also has to consider the manatees that frequently use the river as well as the trash that often clogs it. He said the design will try to capture the trash but also allow manatees to pass.

Preliminary design work on the stations should be done in August with construction completed in December 2026, he said.

Public comment on the plan can be emailed to resiliency@sfwmd.gov.