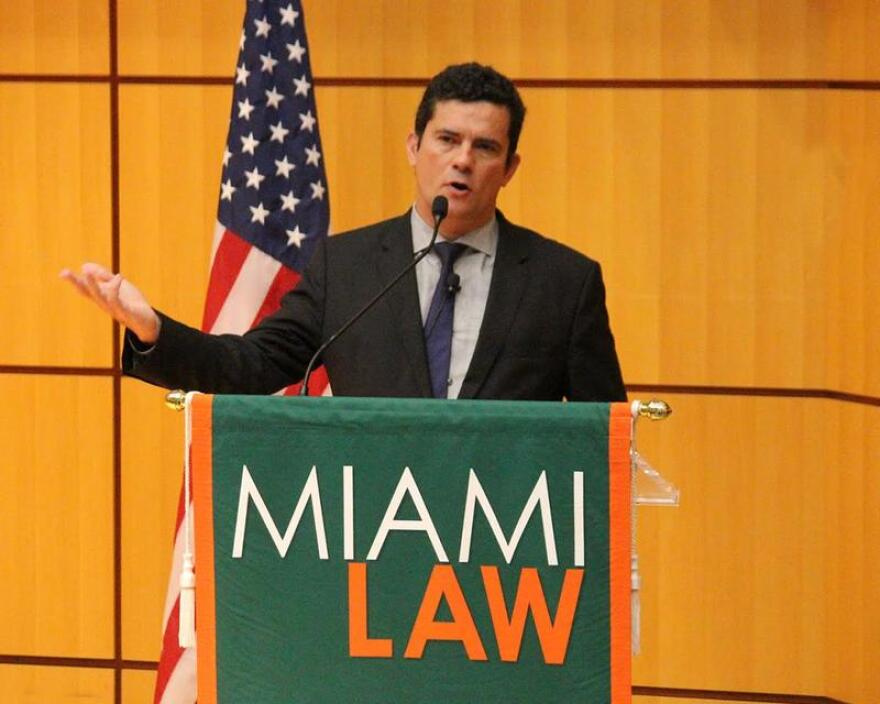

When Sergio Moro gave a lecture at the University of Miami last year he got a loud, standing ovation — because what he was doing in Brazil struck a loud, resounding chord in South Florida.

Moro was the man who was draining the deep, fetid swamp of corruption in Brazil.

In Brazil, as in a lot of Latin American countries, judges are also investigators. Moro was the federal magistrate leading the prosecutions in Brazil’s massive, multi-billion-dollar corruption scandal known as Lava Jato, or Car Wash. For the first time in Brazilian history, scores of top political and business figures of all political stripes were going to prison — including popular former President Luiz Inácio Lula da Silva.

To his Miami audience, Moro was taking down the kind of endemic white-collar criminality that prompts so many people to migrate here from Brazil and the rest of Latin America. And so he ended his UM speech triumphantly.

“The corruption uncovered in Brazil is shameful, no doubt about that,” Moro said. “But maybe the age of Brazilian robber barons is coming to an end.”

READ MORE: Latin America's Anti-Corruption Wave Is a Good Thing. Except When It Isn't.

“What Moro did was really revolutionize Brazilian criminal procedure,” says Keith Rosenn, the emeritus professor at UM’s law school who invited the Brazilian crusader to speak.

"Moro’s a very honest person who really is very concerned about rooting out corruption,” says Rosenn, a Brazil expert who points out a big reason Moro was so successful was that he adapted U.S. prosecutor tactics like plea bargaining to the Brazilian system. “I still believe that Moro did a very good job.”

That assessment of Moro is now coming into question, however.

Moro abused the criminal code process to put Lula in prison. I believe he betrayed Brazilian democracy. — Catarina Bonatto

And the skepticism got a big push last week with the debut of the documentary “Edge of Democracy” on Netflix, which has garnered strong international media buzz.

“Edge of Democracy” suggests that last year’s election of right-wing populist Jair Bolsonaro as president of Brazil — he is often described as Brazil’s Donald Trump — could spell the end of the country’s democracy, which is only 34 years old.

"Today, I fear our democracy was nothing but a short-lived dream," says the documentary's narrator and director, Brazilian filmmaker Petra Costa, in its introduction.

Just as important, the film asserts that Moro — who is now Bolsonaro’s justice minister — imprisoned former President Lula, who heads the leftist Workers Party, or PT, to keep Lula from running against Bolsonaro.

Moro brought back to Brazil the concept of what is right and what is wrong. The people who want to split up Brazil are the people with Lula. — Maria Azeredo

Many Brazilians, in Brazil and in the large South Florida diaspora, share that belief.

“Moro abused the criminal code process to [put] Lula in prison,” says Catarina Bonatto, who was a lawyer in Brazil before moving here to Doral a decade ago. Lula’s conviction, she insists, “was a political judgment.”

As a result, Bonatto demonstrated against Moro’s visit to UM last year, arguing that he used unlawful evidence methods to prosecute Lula on charges he received a luxury apartment as a bribe.

That claim against Moro got bolstered this month with the public leak of some of his emails, which suggest evidence may have been manipulated. (Moro denies any wrongdoing.)

Brazilians like Bonatto feel that alleged manipulation also insults people like her father who fought against Brazil’s brutal, 21-year-long military dictatorship, which ended in 1985.

"I feel Moro betrayed Brazilian democracy too," says Bonatto.

She remembers her father hiding dissidents wanted by the military regime in a house he owned in São Paulo.

“When I was 4 or 5 years old,” she recalls, “my mom never allowed us to go to his house because he had, like, 20 people living in his little house — to save their lives.”

RIGHT AND WRONG

The caveat here, though, is that the center-left Bonatto has supported Lula and the PT. So does the filmmaker Costa, whose “Edge of Democracy” documentary is told largely from a PT viewpoint. And so do the folks who leaked Moro’s emails.

The reality is that many Brazilians — especially in South Florida, where the vast majority of expats support Bolsonaro — still consider Moro a corruption-busting hero who, with or without the Lula case, helped save their country’s democracy.

“I believe what Moro did was bring back in Brazil the concept of what is right and what is wrong,” says expat Maria Azeredo.

Azeredo and her family are conservative evangelical Christians who have a sign-making business in Doral. They voted for Bolsonaro – and they strongly disagree with Costa’s documentary.

“It’s a lie,” says Azeredo's mother, Rubia Azeredo. “Brazilian democracy was betrayed by Lula, not Moro.”

Maria Azeredo acknowledges that Brazil, Latin America’s largest country, is a bitterly polarized place today — “a lot like the United States,” she says. But she points out Lula and the PT were in power from 2003 to 2016 — and that was too long, she says, especially given the leftist party’s own, admittedly widespread corruption.

“The people that want to split up Brazil are the people that are with Lula,” she insists. “Bolsonaro people just wanted something new — like when the Democrats here need to be replaced by Republicans.”

Lula is still appealing his conviction from prison. But whether or not Lula is guilty, and whether or not Moro broke the rules while prosecuting him, this controversy at least lets Brazilians pause and assess what their democracy has done right — and wrong — in the fight against some of the worst corruption in the Americas.