The most important thing in Angela Samuels’ life is staying cool. During the sweltering summer days, she finds momentary relief in the over-chilled air of the mall or grocery store. But come nighttime, there’s no escape from the hot, humid South Florida air.

She counts the public housing unit she stays in as a blessing, but unlike many apartments in South Florida, hers didn’t come with air conditioning.

This summer, as Florida experienced the hottest summer on record, the heat overwhelmed 56-year-old Samuels, who lives in the Edison Courts development just west of Miami’s Little Haiti neighborhood. She had to be rushed to the hospital. Doctors said it was dehydration from sweating so much.

“I would wake up sweating, my entire body would be wet like I had been in the pool,” Samuels said. “It’s over 100 degrees out there, why do they put us in these hot places?”

The advent of air conditioning is what made Florida’s population boom possible. But despite rising temperatures that make AC standard in just about every business and suburban home, it’s long been a different story in public housing.

Federal government rules largely ignore extreme summer temperatures in Florida and elsewhere. They require all public housing to provide heating — but not cooling. They explicitly do not pay for wall units or compensate residents, many of them already struggling to get by, for the higher power bills AC units produce. The U.S. Department of Housing and Urban Development, which funds public housing projects, acknowledged to the Miami Herald that it is reviewing the current rules on AC.

With the growing realization that climate change is driving temperatures dangerously higher, local governments have been forced to come up with their own money to keep residents safe and cool.

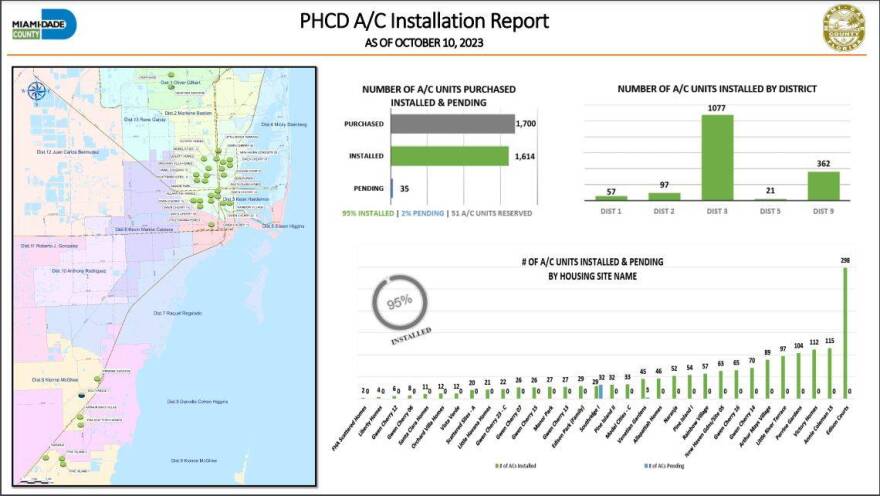

Miami-Dade County recently spent $2.3 million to purchase and install 1,700 new wall-unit air conditioners in its nearly 10,000 public housing units around the country. When the final one is installed later this year, the county claims each and every one of its public housing residents will have access to AC — a milestone that would put it among national leaders in often underfunded public housing programs.

“Every unit in public housing, after our initiative is complete, will have an AC in the unit in one form or fashion or another,” said Alex Ballina, director of the county’s public housing and community development department.

And, Miami-Dade told the Miami Herald, the county pledged to fill any remaining gaps, potentially by tapping the county’s general fund next year.

“In South Florida, air conditioning is a necessity,” said Mayor Daniella Levine Cava. “It is a matter of necessity and dignity. We are housing people, it’s on us to be sure that they have a safe, healthy environment. I take it very seriously.”

PROGRESS AFTER NEARLY A CENTURY

The county’s recent push to help cool its public housing residents is a welcome and long-awaited one.

Back when the first public housing development in the southeastern U.S. was built — in Miami’s Liberty Square development in 1937— air conditioning wasn’t invented yet. And fifty years later, when Trenise Bryant grew up there, that aging development still didn’t have air conditioning.

Bryant took her personal experience in public housing and used her passion as fuel for work on the ground as an executive director of SMASH, a housing justice organization in Miami. In the decades-long absence of local or federal support for air conditioning in older public housing units, organizations like hers tried to step up to fill the gap.

It’s not just a question of comfort. Lack of AC is a health risk, especially for the elderly, the sick and young children, who make up a substantial portion of public housing residents. Hot housing can cause illnesses and even be deadly. During the 2021 heat wave in the Pacific Northwest, a woman living in public housing died of heat stroke. Her unit didn’t have AC. In Miami-Dade, her sweltering un-air-conditioned apartment sent Angela Samuels to the hospital.

Despite the fact the county was actively installing new AC units at the time, Samuels’ first call from the emergency room was to Trenise Bryant. Within days, Samuels had a brand new wall unit for her living room.

“I know what she’s dealing with, people are strapped with limited funds,” Bryant said. “I think AC, any heating or cooling element, should be a human right whether it’s in market rate or public housing, and it should be accommodated for all.”

Miami-Dade is one of a handful of communities across the nation that have found money to add air conditioning to public housing. In this case, the $2.3 million came from the American Rescue Plan, a Covid relief initiative that unlocked billions in federal funds for all kinds of projects.

Miami-Dade started work on the project in November 2022 and said it would take 90 days to install AC in all 1,700 units that did not have it already. When the Herald initially asked about the status of the project in August — in the middle of a record heat wave — the county did not initially reply. But in September, the county said that it had 500 units left to install.

As of last week, the county confirmed to the Herald it had 35 units left to install. A bulk of the installations appear to have occurred this summer, which broke heat records left and right.

At public housing complexes, some residents told the Miami Herald that they were excited about their new air conditioning units recently installed by the county. One resident at Edison Court, who declined to give her name, told the Herald the county-provided AC had made a “big difference” in her apartment.

“It’s nice and cool now,” she said.

‘NO CHOICE’

Despite the welcome addition of all those new AC units, some residents and advocates said they had no idea the county was even handing them out.

“This is the first year that people are talking about the heat being so bad,” Bryant said. “I don’t know if the county did a good job of announcing giving ACs to public housing, and how well it was advertised to the community.”

Other problems in the county’s roll out remain, including the practical challenge of installing AC units in nearly 100-year-old buildings that were never designed for central air.

And for some residents, one wall unit just isn’t enough. Samuels was thrilled to have her new AC unit when she returned from the hospital this summer, but despite the three fans she kept blowing around the clock and her watchful eye on open doors and windows, she was still too hot to sleep.

Bryant offered a second AC unit for her bedroom, but management at Edison Courts said it wouldn’t be allowed. So Samuels dragged her bed into the living room close to the AC to try to catch some of its flow.

When asked about why a public housing development would ban its residents from installing their own AC units, Ballina said the county is beholden to other federal safety rules too, like making sure every room has an escape route for emergencies like a fire. A wall unit would block that exit, he said.

As a workaround, Ballina said the county is exploring wall-mounted AC units that don’t block the window, like the ones commonly seen in hotels. They tend to be more expensive than window units.

While Miami-Dade was working to install units, the process still wasn’t fast enough for some residents — who shelled out for units themselves to make the units tolerable. And the reality is that many of those units are old, inefficient and inadequate to deal with the demands of record summer heat,

Shantasia Miller has lived with her kids for over two years at Victory Homes, a 148-unit complex. She purchased two AC units herself and planned to buy a third once she saved up enough money.

“I had no choice but to buy the ACs,” Miller said. “I don’t want my kids getting a heat rash.”

But no matter who purchased the air conditioner, the monthly power bill falls on the residents themselves — a burden for many low-income residents. HUD told the Herald that it is explicitly barred from paying for the cost of air conditioning for resident units, “ except in the case that elderly or disabled households necessitate it as a reasonable accommodation.”

“For units where the housing authorities pay for utility expenses, families must be charged a surcharge or otherwise pay for the specific costs associated with air conditioning,” the agency wrote in an emailed statement.

A 54-year-old longtime resident of Edison Courts who declined to give her name told the Herald that the one AC unit she had was ruined during Hurricane Irma in 2017. It’s still broken, but she did manage to scrape together enough cash to buy a second unit for her bedroom.

She said she can “barely” afford the $230 monthly utility costs, part of which is covered by a monthly utility stipend the county covers for all units. The stipend is a set amount, so any additional costs — like adding an AC unit — can force some residents to take on an out-of-pocket cost.

“I went years without AC because I couldn’t afford to turn it on,” she said. “I had no choice.”

A NATIONWIDE PUSH FOR AC

While the struggle to update older buildings continues, the future of new construction public housing seems a bit cooler. Since 2001, all newly built or redeveloped public housing in Miami-Dade is required to have central AC.

Liberty Rising, the newest public housing development in Miami-Dade, debuted in 2019 with central air for all units. It was a massive upgrade from the scattered collection of houses built in 1937 that made up Liberty Square, the oldest — and residents say, hottest — public housing development in the southeast.

That’s important in a region that’s expected to get hotter and hotter as unchecked climate change heats the globe. Miami-Dade already experiences about 50 more days a year over 90 degrees than it did in 1960, according to a county report released last year. By 2050, if nothing changes, Miami-Dade could see another 50 more days a year of hot days.

But despite Miami-Dade’s push to cool its public housing, the rest of the nation still lags. HUD has hinted it might change its policies in the future, but there’s no official rule-making process underway.

“HUD is reviewing its policies related to AC in public housing to determine future action,” the agency told the Herald in an emailed response.

Recently, the agency defined a “heating standard” for the first time, which requires landlords in public housing to maintain a certain temperature inside units when it’s cold outside. The agency did not set a cooling standard.

As a result, efforts to provide AC to older public housing developments across the country have looked a lot like Miami-Dade’s.

After HUD denied a budget request to install 2,400 AC units in San Antonio, Texas, the city scraped together $1.5 million in city budget and matching philanthropic pledges to install all the units in 2019. Bills to mandate, or at least encourage, AC in subsidized housing across Texas have failed the last two years in a row, after affordable housing providers said it would be too hard to do.

No such bill has advanced in Florida.

And despite Miami-Dade’s big investment in cooling its public housing residents, thousands of residents are still relying on old, inefficient units they purchased themselves. Ballina said the county has reserved “a few” of the air conditioners to hand out to residents as an upgrade, which they advertised with a flyer posted in some of the public housing developments.

“We can replace what you have existing with the new, more efficient and better quality air conditioning unit, which is better for them as well because it allows them to save on the utility costs,” he said.

Once that pot of cash runs out, Levine Cava said she’s planning on building the cost of new AC units into next year’s county budget.

“It’s a relatively small expense for a huge impact on our residents,” she said.