The American education system seems to be in perpetual crisis. Despite nearly 15 years of education reform – and the introduction of an array of tests, curriculum, and new measures of student learning – students are not any better prepared to succeed in college or the workforce.

And the bad news just keeps coming.

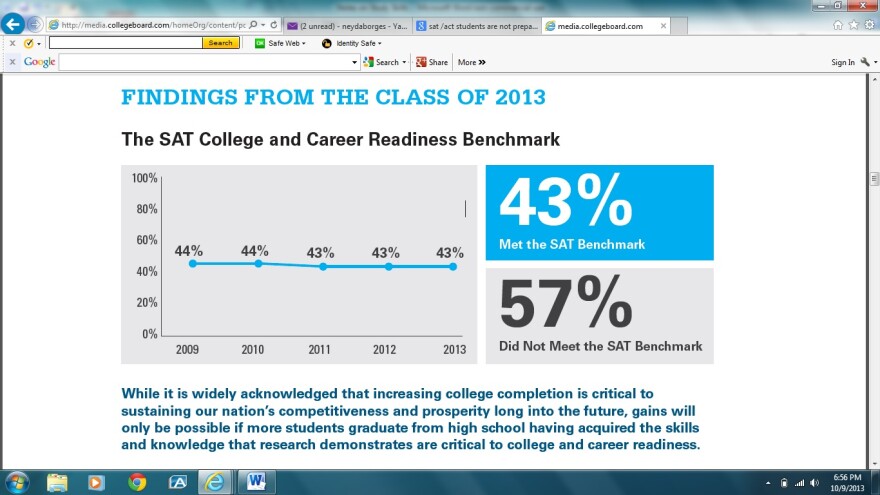

Annual SAT scores released to the public demonstrate a continued decline in math and writing scores. In the data released by the College Board, 57 percent of graduating seniors are not ready for college.

Technically, the 2013 results are nearly identical to those released in 2012 which were -- until now -- the lowest average SAT score since The College Board began keeping records in 1972, part of the reason why the SAT will be revamped in 2015 in order to become more relevant to what students are learning – and what they need to learn to succeed in college.

But, it’s not just the kids that are unprepared; grown-ups are in trouble too.

A new study shows that Americans are lagging behind other democratic countries in literacy, math and technology. The new tests, developed by the Organization for Economic Cooperation and Development (OECD), surveyed 166,000 teens and adults ranging in age from 16 to 65 years old in 24 countries. The survey measured literacy, math and computer skills.

The results don’t look good. Americans are “decidedly weaker in numeracy and problem-solving skills than in literacy, and average U.S. scores for all three are below the international average and far behind the scores of top performers like Japan or Finland,” said Jack Buckley, commissioner of the National Center for Education Statistics, the data collection arm of the U.S. Department of Education.

The United States ranked near the middle in literacy and near the bottom in skill with numbers and technology. In number skills, just 9 percent of Americans scored in the top two of five proficiency levels, compared with a 23-country average of 12 percent, and 19 percent in Finland, Japan and Sweden.

“These findings should concern us all,” said Education Secretary Arne Duncan in a written statement. “They show our education system hasn’t done enough to help Americans compete — or position our country to lead — in a global economy that demands increasingly higher skills.”

Puzzling is that older Americans, those aged 55-65, scored better than their younger counterparts. This may be the first generation which does not surpass their parents’ generation in education or skill level.

"In the U.S., the older generation was one of the most highly skilled, but the younger generation does worse than average," said Mr. Andreas Schleicher, deputy director for education and skills at the OECD.

This education deficit will translate to an economic issue.

“Adults who have trouble reading, doing math, solving problems and using technology will find the doors of the 21st Century workforce closed to them,” Duncan said. “We need to find ways to challenge and reach more adults to upgrade their skills.”

Another similarity between the grown-ups and our kids? There were significant differences in test scores between whites and minorities, between Americans in high income households and low.

"In both reading and math, for example, those with college-educated parents did better than those whose parents did not complete high school," reported the Associated Press, which also added, “the findings reinforced just how large the gap is between the nation's high- and low-skilled workers and how hard it is to move ahead when your parents haven't.”

The same is true for American school children. Gaps persist by racial and ethnic groups, with Asian and white students far outperforming African-American, Hispanic, Pacific Islander and American Indian students, which are far more likely to live in impoverished neighborhoods.

And, in our very own communities, a Miami Herald study showed that over the last 14 years, schools in the wealthiest neighborhoods never get Fs, while the county’s D and F schools are overwhelmingly serving students from poor neighborhoods.

Similarly, the incomes of Americans who scored the highest on the OECD’s literacy tests are on average 60 percent higher than the incomes of Americans with the lowest literacy scores, who were also twice as likely to be unemployed.

Do the OECD scores mean that the U.S. is doomed?

No. It does, however, highlight a problem with our education system. It is not that the United States is getting dumber; it is that other countries around the world are making great improvements in education and their labor force is increasingly better prepared for the global workforce. We, on the other hand, have stood still.

While we are testing students more than ever before, they are not any smarter for the wear.

The test scores also illustrate another problem that permeates our public education system. There is a growing chasm between the poor and the priveleged. And, it is becoming increasingly difficult to ignore. Not only is there a huge difference in test scores – on the SAT, ACT and even the OECD – but in college acceptance and retention, as well as employment.

And, as robots and machines take the place of people, and both high and low-skilled manufacturing work moves overseas, it may become increasingly difficult for people to find work, which will definitely translate to a huge economic problem.

Closing the achievement gap then, is not just a moral imperative, but a financial one as well.