Some parents see it coming. Natalie was not that kind of parent.

Even after the director and a teacher at her older son's day care sat her down one afternoon in 2011 to detail the 3-year-old's difficulty socializing and his tendency to chatter endlessly about topics his peers showed no interest in, she still didn't get the message.

Her son, the two educators eventually spelled out, might be on the autism spectrum.

"I was in tears at the end," she says. "When I got home, I was just devastated."

Natalie broke the news to her wife, Stephanie, whose mind fast-forwarded to a distressing future. Would her son — a squat, cheerful boy who, despite his affectionate nature, didn't have any playmates — ever be able to make friends?

When a doctor eventually confirmed he had an autism spectrum disorder, the diagnosis came with a suggestion: Perhaps the boy would benefit from Prozac when he turned 7.

"That was when both of us fell apart in that meeting," Natalie says. For both parents, medication wasn't an option.

"Prozac is a very powerful drug for adults. Why would you give it to a 7-year-old?" Stephanie wondered after the doctor's visit. "I welled up with all of this emotion. And I said I will not let that happen."

(To protect their privacy, we are only using Natalie's and Stephanie's first names. We are not naming their children.)

The fear of psychotropic drugs led the family to pursue alternative treatments for autism.

To start, they dropped gluten.

Then one day, as Natalie roamed the aisles of a gluten-free expo in a Chicago suburb not far from where the family lives, she came across a booth for a Brain Balance Achievement Center.

Natalie says the program claimed to help with disorders ranging from dyslexia to ADHD and autism. Best of all, it didn't involve prescription drugs.

"We were very excited," Stephanie says. "Maybe we found a solution that wasn't going to be about medicine. I was very, very hopeful."

" It will completely, absolutely, 100 percent change your life"

Natalie had stumbled upon one of 113 Brain Balance franchises across the country. Seventeen more are in the works. In the dozen years since its inception, Brain Balance says, it has helped roughly 25,000 children. The company says it is currently taking in over $50 million in annual revenue.

Although Brain Balance isn't the only purveyor of alternative approaches for developmental disorders in the U.S., the scale of the enterprise sets it apart. The company's approach is still relatively new and not widely known, meaning many experts in the field of childhood development have not vetted its effectiveness.

Brain Balance says its nonmedical and drug-free program helps children who struggle with ADHD, autism spectrum disorders and learning and processing disorders. The company says it addresses a child's challenges with a combination of physical exercises, nutritional guidance and academic training.

An NPR investigation of Brain Balance reveals a company whose promises have resonated with parents averse to medication. But Brain Balance also appears to have overstated the scientific evidence in its messaging to families, who can easily spend over $10,000 in six months, a common length of enrollment.

Brain Balance's metrics for consumer satisfaction are impressive. Customers rate the program, on average, an 8.5 on a 10-point scale in surveys, according to the company.

The ratings square with comments in online forums and in interviews NPR conducted with 18 parents who enrolled their children. Across the country, about three dozen centers are run by parents who began as happy customers.

Brain Balance's website is where caretakers encounter the company's strongest pitch: dozens upon dozens of parent testimonials.

One of the company's television commercials begins with a montage of formerly frustrated mothers. But, they all agree, Brain Balance put an end to their kids' challenges. One woman insists "it will completely, absolutely, 100 percent change your life."

Autism "can become a thing of the past"

The man who created Brain Balance, Robert Melillo, is often introduced as "Dr. Melillo" in media appearances. He has a doctorate and an active license in chiropractic. He is also acknowledged as an expert in the field of functional neurology, chiropractic's controversial alternative to mainstream neurology.

Melillo's biography states he has master's degrees in neuroscience and clinical rehabilitation neuropsychology, though it does not say from where. A curriculum vitae for Melillo that NPR found on a website for chiropractic licensing boards says the master's in neuroscience came from the Carrick Institute for Graduate Studies, a chiropractic academy in Florida that isn't accredited by any of the agencies recognized by the Department of Education. His second master's degree is from a now-defunct program at Touro College, a private educational organization based in New York.

This isn't smoke and mirrors. This is real stuff.

Melillo says it was during an intense period of research in the 1990s, while his own son struggled with attention issues, that he conceived of a single disorder to explain everything from autism to ADHD to dyslexia. He called it functional disconnection syndrome.

As he writes in his book, Disconnected Kids, the syndrome occurs when "areas in the brain, especially the two hemispheres of the brain, are not electrically balanced, or synchronized." The particulars of this imbalance are not clearly defined in the book, but numerous metaphors — some involving concert orchestras with bad timing or tuning — paint a picture of a child's brain unable to communicate with itself.

According to Melillo, a weak right hemisphere (the emotional half) can lead to autism and ADHD; a weak left hemisphere (the logical half) often causes learning disorders like dyslexia.

And he argues in the book that for people who follow his program, "ADHD, dyslexia, and even autism, among others, can become a thing of the past."

He even appears to see his program as the answer to societal problems.

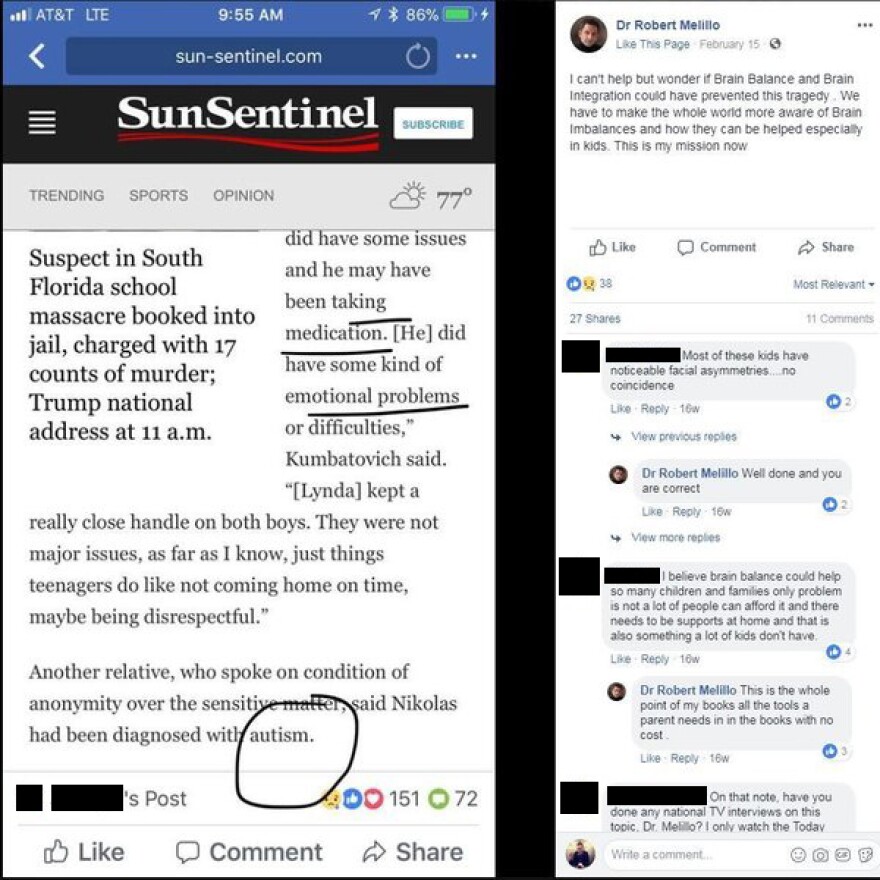

In February, one day after the mass shooting at Marjory Stoneman Douglas High School in Parkland, Fla., Melillo used his public Facebook page to envision a world where Brain Balance had reached the shooter.

"I can't help but wonder if Brain Balance and Brain Integration could have prevented this tragedy," Melillo wrote in the post alongside a news report in which the shooter's relatives said the teenager had been diagnosed with autism and took medication.

"We have to make the whole world more aware of Brain Imbalances and how they can be helped especially in kids," he added. "This is my mission now."

What happens at Brain Balance

Stephanie and Natalie say they watched their older son from the other side of a two-way mirror as a Brain Balance staff member ran him through a series of tests during his baseline assessment. Later, they received his results: eight pages of ratings in unfamiliar categories.

"I have two master's [degrees] and a Ph.D., and I needed them explained to me," Natalie says. Their son had a weak right hemisphere. Additionally, his "frontal lobe acquisition" was lacking. His primitive reflexes were also in bad shape, according to the assessment, portions of which were shared with NPR.

The center recommended six months of one-hour sessions three times a week, a common course of intervention.

Brain Balance's approach breaks down into three broad categories: academic, nutrition and sensory-motor.

The academic exercises focus on the same areas targeted by many after-school tutoring programs. The nutritional component recommends decreasing a child's intake of gluten, dairy and refined sugar.

The third, and most complex, prong of Brain Balance's intervention is its sensory-motor training, a diverse set of physical exercises. Parents and former employees describe activities like walking across balance beams, syncing actions with a computerized metronome and being spun in swivel chairs.

Consistent with Melillo's theory, Brain Balance focuses much of its sensory-motor training on one-half of the child's body to send strengthening signals up and across to the supposedly weak, opposite hemisphere of the brain. (Much of the human brain indeed maps to the opposite half of the human body.)

For instance, with a "right brain weak" child like Stephanie and Natalie's son, Brain Balance may have him wear a vibrating armband on his left biceps or eyeglasses that allow light only onto the left visual field. Or they may simply have him stand on his left leg.

It has not been uncommon for parents to enroll their children for at least six months, costing roughly $12,000. The company recently said its average enrollment is now about four months. Assessments and optional nutritional supplements and blood tests can add hundreds of dollars.

The program isn't covered by insurance. Brain Balance offers payment plans to parents who can't cover the cost immediately. As of publication, close to 200 families have solicited money from relatives and friends with GoFundMe.com campaigns.

Natalie and Stephanie were quoted $5,000 for their first three months, with the option to re-up for more after.

"When you're talking about your child's self-esteem and knowing it's the most important thing, what are you going to do?" Stephanie says. "Maybe work a few more years and take a little bit out of your retirement so that maybe — if you nip this thing in the bud — he's able to have a better life going forward?"

They dipped into their retirement savings and enrolled both their sons at a total cost of more than $15,000.

" Cutting edge" science

In numerous media appearances, Melillo hasn't been shy about publicizing the strength of his program's scientific evidence.

"This isn't smoke and mirrors. This is real stuff. ... [Parents] are going to get real answers," Melillo told a radio host in 2010. "We've shown in our centers that we can correct these problems completely. We've proved that in research," he said on TV in 2014. "We use really cutting-edge brain science to address the issue," he said in 2016.

Yet a dozen experts in autism spectrum disorder, ADHD, dyslexia and childhood psychiatry interviewed by NPR all identified flaws in Brain Balance's approach.

They said the company's idea of imbalanced hemispheres was too simplistic and built upon the popular, discredited myth of the logical left brain and the intuitive right brain.

"It doesn't make sense," says Mark Mahone, a pediatric neuropsychologist at the Kennedy Krieger Institute in Baltimore. "In virtually every activity that one does ... both hemispheres of the brain are very, very active. ... It's not as simple as just being a left- or a right-hemisphere problem. Nothing is that simple."

As for the three-pronged Brain Balance regimen, experts NPR spoke with said there is no solid evidence suggesting gluten, dairy or sugar consumption affects ADHD, autism or dyslexia. And although physical exercise may have modest impacts on inattention and tutoring can help in school, these interventions can be found elsewhere for much less money. No expert suggested either as a front-line remedy for ADHD or autism.

Doctors and researchers NPR interviewed also questioned the diagnostic metrics Brain Balance uses.

For example, the company tests children for the primitive reflexes that drive infants to instinctively suckle or grab a finger. Natalie and Stephanie were told their son's lingering primitive reflexes were connected to his behavioral issues.

Learn what Asymmetrical Tonic Neck Reflex is and what the warning signs are. https://t.co/KE7CbsE8Hq #BrainBalanceCenters #ATNR #dyslexia pic.twitter.com/3TXCz3h6Mz

— Brain Balance Centers (@Brain_Balance) January 18, 2018

But multiple pediatricians said it is exceptionally rare for children older than 4 to retain any primitive reflexes.

"Typically by 1 year of age these primitive reflexes have disappeared," says Dr. Andrew Adesman, a developmental pediatrician at Cohen Children's Medical Center of New York. "The major exception is children who have cerebral palsy."

Melillo disagreed with the experts' opinions. "I think they're completely wrong," he says.

"Pediatricians rarely look at primitive reflexes after infancy, but if they did, they will find that, in many cases, they are still there," he wrote in an email.

Melillo also pushed back against the medical consensus that autism, ADHD and dyslexia aren't caused by hemispheric differences and that gluten doesn't affect such disorders.

"I can show you a lot of papers that actually say that there is a relationship between food sensitivities, gluten sensitivity and different types of issues and conditions," he says. "So again, it depends on the expert."

" Evidence based"?

There are two published studies of Brain Balance, which the company has said show that 81 percent of children with ADHD no longer displayed symptoms after three months in the program.

"We have two studies now," Melillo said on local TV in 2013. "So that means that we qualify as what we call 'evidence based' at this point."

Brain Balance touted one of the studies on its blog with the headline, "Control Study Shows Brain Balance Eliminates ADHD Symptoms."

The studies, however, have serious scientific shortcomings.

Melillo, someone with a clear financial interest in the outcome, co-authored the first one.

He also had parents rate their own children's improvement in ADHD symptoms but didn't compare them with other kids who weren't in Brain Balance.

Without a control group, a study cannot definitively determine whether an intervention — a pill or procedure or program — is the reason for improvement or whether any change is simply the placebo effect.

The second study did feature a control group of children with ADHD who didn't do Brain Balance. But it compared them with the same children from the first study published years earlier instead of randomly assigning children into simultaneous treatment and control groups.

"My issue with these data is that there's no legitimate comparison for the treatment group, so we really don't know if [Brain Balance] helps," says Dr. Paul Wang, deputy director for clinical research at the Simons Foundation.

The experts NPR consulted took issue with other aspects of the studies as well.

It means absolutely nothing. ... What we have here, in my view, is a marketing piece.

The kids in the treatment and control groups differed in important ways, the experts said, rendering comparisons between them less meaningful. The two groups weren't drawn from the same centers; all of the treatment group was medicated while only 60 percent of the controls were; and at baseline the controls scored more severe on an ADHD rating scale.

Curiously, even though the second study reused the treatment group data from the first study published years earlier, it reported different improvements on those same kids' test scores. The lead author on both studies, Gerry Leisman, a professor of neuro and rehabilitation sciences at the University of Haifa in Israel, explained one of the test score differences as a "reviewer correction" but did not provide explanations for any of the six remaining discrepancies.

Dr. James McGough, a professor of clinical psychiatry at UCLA's David Geffen Medical School, wasn't convinced by Brain Balance's published research. "It means absolutely nothing. ... What we have here, in my view, is a marketing piece."

At least one state remains similarly unconvinced.

In 2015, Wisconsin's Department of Health Services determined Brain Balance had " insufficient evidence" to show it was a "proven and effective treatment for individuals with autism spectrum disorder and/or other developmental disabilities," as the Milwaukee Journal-Sentinel reported. The state assigned Brain Balance to the second-lowest ranking on its five-tier system. The only lower ranking is for "potentially harmful" treatments.

Brain Balance defends its approach

Asked by NPR why Brain Balance hadn't been tested more thoroughly before its nationwide expansion began a decade ago, Melillo says the company was "faced with a dilemma." While he did feel an obligation to validate his approach, he says he knew Brain Balance worked and didn't want to deprive his clients of its benefits while waiting for clinical trials. "All these 25,000 families that we've helped, are they left suffering for years on end?"

"What was done to date was commensurate to the resources that we had," says Aleem Choudhry, the chairman of Brain Balance and a managing member at Crane Street Capital, which invested in the franchise in 2013.

The company says ADHD was the only disorder to be studied thus far because — contrary to the opinion of all the experts contacted by NPR — it is neurologically equivalent to others like autism, dyslexia and OCD. If Brain Balance improves ADHD symptoms, Melillo says, "then we believe that we're going to get the same results in the other types of issues, because they're really the same problem."

Melillo also says the company's proprietary records from about 80,000 before-and-after client assessments qualify as corroboration. Melillo disputed the idea that his company's own data may require third-party review. "Data is data," he says. "There's no bias in the way we collect this."

A new study of a computerized version of Brain Balance is underway at a Harvard-affiliated hospital and features a concurrent control group of children.

But Melillo says that questions about the research behind Brain Balance ultimately miss a larger, more important point.

"Families are out there struggling and suffering, and they don't really give a crap about the data or the research, to be quite honest," he says. "When they go through it and they see the difference in their child ... that's what matters to them."

Choudhry, the company's chairman, later clarified that "we very much do care about the data."

No easy answer

With both their boys enrolled in Brain Balance, the routine for Stephanie and Natalie's family was frantic.

Three times a week, Stephanie would ferry their sons against traffic to and from their sessions. Family dinners became more rushed. Soccer and swimming were abandoned.

Lost time is often a hidden cost of any form of treatment.

The mothers began observing changes in their older son. They say his previously weak sense of smell suddenly blossomed, first for brownies and then other foods. And he became less obsessed with characters he had repetitively sketched in his notebooks and imbued with rich inner lives. (His parents are torn as to whether this was a positive development.) He also advanced in certain Brain Balance measures, including his primitive reflexes.

"It's not that the needle didn't move on some of those dimensions," says Natalie. "But if you step back at the 10,000- or 100,000-foot view and say, 'Is this kid different in a way that his life is going to be better or altered?' the answer is 'No.' OK, so now he can smell brownies that he couldn't smell before but is his life different?"

She says she and her wife began to feel discouraged, thinking about the "aura around this program that says your child's going to be different and better-adjusted."

Eric Rossen of the National Association of School Psychologists isn't surprised by Brain Balance's popularity as an option beyond what schools and insurance will cover.

He says many parents are frustrated by mainstream medicine's limits when it comes to complex disorders like autism. And schools are sometimes too strapped for resources to provide students with learning disorders all the help their parents may want.

"Most parents will say they would die for their children," Rossen says. "So to say, 'I want to provide some therapy and pay a few thousand dollars' is quite short of dying for them and it's totally reasonable."

But he says "the problem is they are easy prey for certain providers that can make promises that cannot necessarily be kept or are not necessarily backed by scientific data."

For parents looking to find evidence-based third-party interventions, experts suggest the What Works Clearinghouse, which is backed by the Department of Education, or the Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration's own resource.

Brain Balance's protocol doesn't appear to pose any physical or developmental harms to children. Instead, the program's costs may come in other ways: siphoning away time and money, and prolonging the hope in some parents that their child may one day shed his or her disorder.

Dr. Susan Hyman, a professor of pediatrics at the University of Rochester who has studied autism treatments for decades, says many alternative providers do this by offering an unrealistically simple solution.

"If you were to come to a traditional provider who said, 'You know I'm going to have you work really, really, really hard. ... I might have some drugs. Drugs have side effects. And 90 percent of the time, as an adult, he is still going to have autism,' that's a far less attractive message than 'I can help you.' "

Beyond Brain Balance

By the end of their older son's second three-month session at Brain Balance, Stephanie and Natalie had completely soured on it. They stopped believing that vibrating armbands and spinning in swivel chairs would translate to social success.

They decided to not continue.

Later, in second grade, their older son began to work with a social worker at school who taught him how to have socially acceptable conversation with his peers.

And Stephanie and Natalie did something else — the unthinkable.

They put their son on a medication called Strattera. Calibrating the proper dosage with tolerable side effects was a drawn-out process, but eventually they reached an equilibrium. Their older son ended up with a new diagnosis that has some overlap with autism but is more consistent with ADHD, which the medication treats.

Today, he seems to be navigating the world more successfully than before.

On a Saturday last August, their older son — who once plaintively asked his parents, "Why aren't I invited to birthday parties?" — had just wrapped up a party to celebrate turning 10 years old.

Natalie and Stephanie had pizzas delivered and rented a truck lined with pleather sofas on one side and video game systems along the other. The children sat in pairs and used their greasy fingers to dispatch their avatars against each other in virtual battle.

"They were yelling my son's name and saying 'Come play with me! Come play with me!' " recalls Natalie.

The birthday boy says he invited almost all of his friends, from school and camp, and all but one showed up, which was more than he could have ever imagined before.

"Because," he says before pausing. "I haven't had friends for a bit. Until I got my medicine. I got some treatment. I got help. Now, I have tons of friends."

The reporter, Chris Benderev, can be contacted at cbenderev@npr.org.

Copyright 2020 NPR. To see more, visit https://www.npr.org. 9(MDAyNDY5MjM1MDEyODE2MzMyMTZmZDQwMg001))