The popular new single by recently exiled Cuban singer Haydée Milanés — titled in Spanish “Duele,” or “It Hurts” — starts with the lyrics, “My darling, you don’t know the torment I feel in my soul if I think about you.”

But Milanés isn’t singing to a lover; she’s lamenting the tragedy of her native country, Cuba.

"Duele" — which she sings with the rapper El B, himself a Cuban exile — is a ballad, but it’s also got bile. It denounces the communist dictatorship for the island’s economic suffering and political repression, while its achingly melodic chorus says, “I carry a broken heart for Cuba."

For Haydée Milanés, the broken heart is especially personal because her father was the legendary Cuban singer Pablo Milanés.

In an interview with WLRN, Haydée Milanés said she "wanted 'Duele' to convey that fraught mix of profound love and profound pain my father felt for Cuba himself" — adding that she also considers the song a prayer to Oshún, a goddess of Cuba's Afro-Cuban Santería religion, "to show us a way out of this nightmare."

READ MORE: 'Patria y Vida,' up for a Latin Grammy, leads a protest music boom in Latin America

The elder Milanés, in fact, had once been identified with the Cuban Revolution. But when he died in Spain in 2022 — the same year Haydée left Cuba for Miami — he too had become estranged from the regime.

"In the end he was to a large degree castigado — punished by the revolution for speaking up for its political prisoners," Haydée Milanés said. "And I feel I was then punished for being his daughter — and for my own support of dissidents of my generation."

Cubans can — and do — debate the extent to which once favored performers like Milanés father and daughter broke with Cuba's government when they were still on the island. But either way, Haydée Milanés is a prominent example of an unusually large and recent exodus of Cuban singers, actors and other artists to places like Miami and Madrid.

Last fall, for example, Wilbert Gutiérrez became the last star of the comedy series Vivir del Cuento to come live in Miami — following co-stars like Luis Silva, creator of the iconic character Pánfilo, who once bantered with then U.S. President Barack Obama. Their exit effectively shut down the most popular TV show in Cuban history.

This epic culture drain comes on top of the severe brain drain Cuba was already experiencing, amid a mass out-migration that has seen almost a fifth of the country's population leave since 2021.

The flight has especially emptied Cuba's younger population — so badly that the only demographic growing on the island now is people over the age of 60.

Key turning point

Miami Cuban-American Reuben Rojas, a leading humanitarian aid specialist who has long worked with Cubans both there and in exile, points out the artistic exit may mark an even more key turning point.

"Artists tend to be the last ones to leave Cuba," said Rojas, who has worked with several Cuban artists over the years.

He points out that in the past, the regime counted on artists — like Pablo Milanés, who during his heyday in the 1980s helped found the modern Cuban musical movement known as nueva trova, or new ballad — to show the revolution’s positive face.

The artists, in turn — even in this century, amid Cuba's economic implosion and severe crackdowns on dissent — took at least some measure of inspiration from the revolution’s progressive and egalitarian ideals.

That relationship has now largely vanished, especially after the 2016 death of the Cuban Revolution's founding dictator, Fidel Castro, and the decay of once applauded achievements like its health and education systems.

"The revolutionary imagery that so many artists once fed on is gone," notes Lilly Blanco, a Cuban-American singer-songwriter in Miami and a Latin American music expert.

Rojas agrees: “Cuban artists normally have a little bit more resources, like doctors," he said.

"But Cuba has gone to the brink of extreme collapse. There’s no electricity, there’s no food — and now those artists, too, are repressed by the government," he adds, pointing as a glaring example to the clampdown on the movement of largely visual artists known as San Isidro.

"They’ve had no other choice but to leave.”

"I saw the criminalization of massive but peaceful protest in Cuba — but also the criminalization of art. This feels like a rebirth for me as an artist."Haydée Milanés

The émigré list since just last summer is striking. It includes acclaimed pianist and bandleader Lazarito Valdés, who’s now living in Miami; and popular singer Laritza Bacallao, daughter of the late celebrated Cuban singer Ernesto Bacallao, is now in Madrid.

¡Libertad!

A common impetus behind many of these departures is July 11, 2021.

That day saw the largest burst of street protests ever against the Cuban regime. But it was followed by one of the regime’s largest-ever sweeps of arrests.

Those imprisoned include Luis Otero Alcántara and Maykel "Osorbo" Castillo, two of the artists who wrote the Grammy-winning protest song “Patria y Vida,” or Homeland and Life, that helped spark the July 11 demonstrations.

Which explains why the July 11th marching chants of “¡Libertad!" — or "Freedom!" — end Haydée Milanés' new anti-Cuban regime song “Duele."

“The breaking point for me, too, was July 11," Milanés said. "I saw the criminalization of this massive but peaceful protest — but also the criminalization of art.”

Milanés says she was especially affected by the regime’s crackdown on the San Isidro artists. They had been pushing in overt ways for the kind of freedom of expression in Cuba she feels her famous father Pablo Milanés had urged more covertly.

“I identified with their cause, and I took a risk and complained about their treatment on social media — because I realized this is what my father had been struggling against in his later years," she said.

She says the regime greatly reduced her concert dates — "They wouldn't let me book a show outside Havana," she said — and censured her.

READ MORE: Cuban artists are captivating the world. But can they challenge the regime?

In 2022, Milanés and her manager husband, audiovisual artist Alejandro Gutiérrez, decided they and their young daughter had no future in Cuba, and they made their way to the U.S., where they’re now legal residents.

Since then, Milanés, like so many artists who’ve left Cuba, has experienced her own musical libertad — especially as a songwriter, exploring the myriad Latin sounds that flow through Miami’s melting pot.

Milanés’ newest single — “Un Amor Que Se Demora,” or "A Love Delayed" — finds Milanés blending styles like Cuban son and Dominican bachata worthy of Juan Luis Guerra.

“It feels like a rebirth for me as an artist," she said. "In Cuba I spent years singing certain kinds of songs written by other composers. Now I can experiment. I can express myself.”

And, of course, make a better living at it. And that’s sometimes where the controversy over this Cuban art exodus arises. "That's going to be the touchy subject," says Blanco.

'Timeline of exasperation'

She points out a lot of Cuban exiles are asking why it took so long for Cuban artists like Milanés to see how repressive the island’s regime really is — and why they waited until they were off the island to more clearly condemn that regime.

“Don't get me wrong," Blanco said, "I admire Haydée Milanés if she wants to use the platform of her legacy now to do that. By all means, she should.

"But I just think it’s easier to do that from here than doing it from the inside. And that’s always going to be a thorn in the side” for many Cuban exiles as they watch the island's artists make for the U.S. and Europe.

Milanés argues in turn that Cubans like her simply often hold out hope that the system will finally reform in the face of economic implosion and human rights demands.

“It’s a complicated process," she said, "and each of us has a different timeline for that moment of awakening when you realize that things in Cuba are never going to change ... and that it feels like everything's been destroyed.”

Rojas too acknowledges "that timeline of exasperation can be different for every Cuban."

"And the thing to understand," he said, "is that it can in fact be longer for artists because they've been conditioned perhaps more than other Cubans to take some pride in what the revolution once stood for — and in how resilient the country has been in the most difficult of times.

"But now even they see the system just doesn't work anymore."

Milanés also points out that artists can and are serving an important role as "bridges" between the Cuban diaspora and Cubans still on the island.

"The emotional life for any Cuban, there or here, is always stressful because the political situation complicates everything," she said.

"It's as if we're forced to engage politics even when we don't want to — I mean, I would love to talk about other things in life, but for us it's an overwhelming reality that's impossible to avoid.

"But that's where art and music can help unify Cubans — that's what a song like "Duele" is trying to do."

For many artists, it can be a simpler matter of family unification.

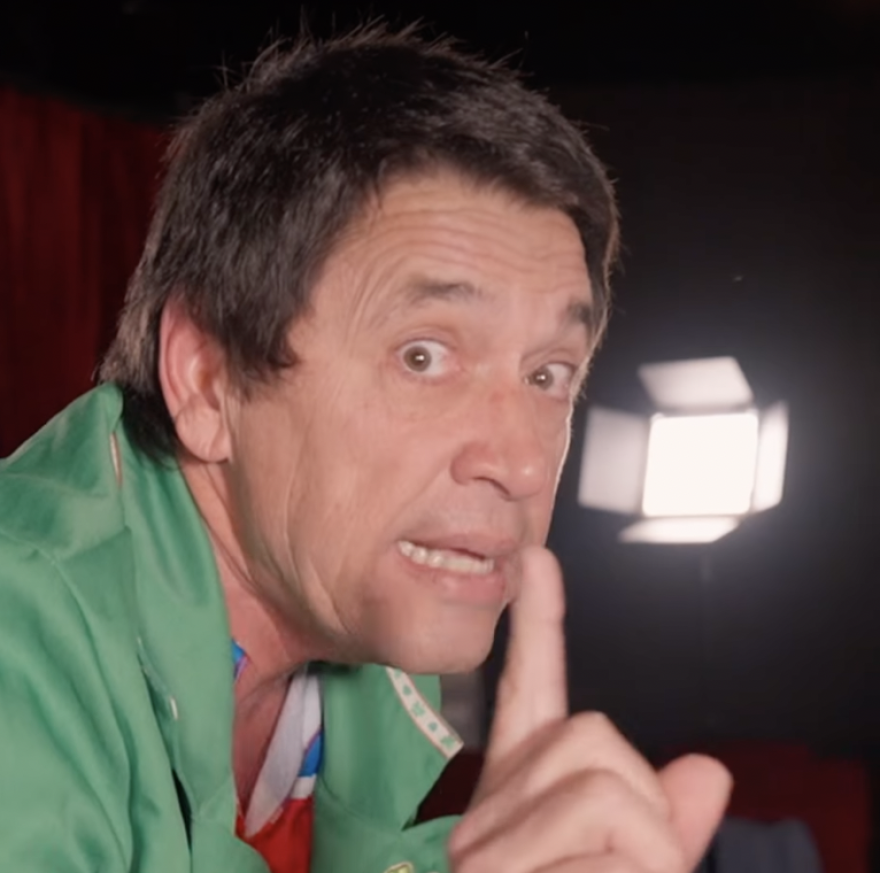

The breaking point, in fact, for popular Cuban stage, film and TV actor Jorge Treto, who is 61, was raw loneliness.

Treto, known for Cuban films such as Inocencia and streaming series like Netflix’s “Four Seasons in Havana," first saw his daughter Laura, also an actor, emigrate to Miami a few years ago. Then his wife Emma, also an actor, joined her.

“It's like I woke up one morning and realized I had no family left in Cuba,” Treto told WLRN.

"And you realize then how everything around you, economically, socially and professionally, has deteriorated to the point of no return."

So last fall he too emigrated to Miami.

“When all the young actors, like my daughter, are leaving Cuba," he added, "you also realize there’s no one there to hand the profession down to anymore."

Treto can now pass it on to a younger generation in Miami. Last month he starred in a play for children at the Trail Theater — on that most Cuban of streets, Calle Ocho.