Several current and former students and their parents describe Miami Country Day School as a place where white children mock and dehumanize their black peers and the adults in charge do little to stop it.

At Miami Country Day School, Sam Caballero took a class in survival skills.

It's an elective in which students learn about camping: how to use a compass and a first aid kit. One day, in seventh grade, her teacher left the room briefly.

"One of the students, he yelled, 'You coon!' " Caballero said, repeating the racial slur her classmate used. "And another student, said, 'Sam, he just called you a coon.' "

Caballero, who has a Jamaican mom and a Puerto Rican dad, had started attending the predominantly white private school in Miami Shores the year before. This was the first time she realized that some of her classmates thought she was different — and less than.

"It hurts me now to think, at that age, I didn't realize what they saw me as. They saw me as a coon," she said. "So that sucks — when you think you're all friends and they laugh at you."

Caballero, now 22, said she faced racist bullies almost every day when she attended Miami Country Day School. In 2012, she left because of it, and years later, the painful memories still flood her with anger, sadness and anxiety.

Her portrayal of a troubling racial climate at Miami Country Day School was reflected in interviews with several current and former students and their parents. They describe a school in which white children mock and dehumanize their black peers, and they say the adults in charge do little to stop it.

The outgoing principal and two teachers at Miami Country Day School said they’re working to make the campus a safer place for students of color. About 5 percent of the 1,250 students in pre-school through 12th grade are black, according to the most recent data available from the federal government.

Administrators said they brought in an expert to assess the school’s climate for students from diverse backgrounds and made changes based on his recommendations. Teachers participate in national trainings on how to make classrooms welcoming spaces. There are extracurricular groups in which black and Hispanic, LGBT and Jewish kids, among others, can share their experiences in safe environments. Administrators have facilitated regular student-led discussions on racism and other forms of injustice.

"Sometimes we deliberately, intentionally take a step forward, and sometimes we kind of stumble forward," said John Davies, who served as head of school for 18 years and retired last month. "We've made great progress, but we have a ways to go."

The Miami school is not alone in facing this crisis.

Combating racism — and creating more inclusive environments for black and brown kids as well as students of different socioeconomic backgrounds, religious faiths, sexual orientations and gender identities — is a top priority for elite private schools nationwide. Experts say that focus has become more intense and urgent since the 2016 presidential election, after which school communities began grappling more openly with the intolerance that’s reflected in broader American society.

"It's part of this tumultuous sociopolitical and cultural time that we're in," said Gene Batiste, who previously oversaw diversity initiatives for a national association of private schools and now works as a Houston-based consultant helping private schools around the country become more diverse and inclusive.

"There's this license to be less civil," he said, "and students are modeling … what they're seeing happening in their political and social discourse."

'I FELT SILENCED, AND I FELT POWERLESS'

Sam Caballero was in fifth grade at a charter school in Liberty City when she won a full scholarship to Miami Country Day School that would take her through graduation.

Before middle school, her classmates had been almost all black kids. Her skin is light, like her father's, and sometimes she was teased by her peers for not being black enough. But her Jamaican mom instilled in her a secure sense of her identity.

"People wouldn’t look at me and think that I am black," she said. "But when I am asked to identify myself on a piece of paper, I always write black, African American. Because that’s how I see myself."

When she got to Miami Country Day School in 2007, though, she was ridiculed for her blackness.

White students made fun of how she talked, called her "ghetto." They asked her questions about black people and culture, "like I’m some sort of encyclopedia for them," she said.

"They would ask me, 'Do black people use cocoa butter, really?' " she said. " 'Why does your hair do this? Did you listen to Lil Wayne’s new album?' "

Caballero said the bullying and constant questioning made her feel depressed and anxious. In high school, she had frequent episodes of intense chest pain that were later diagnosed as panic attacks.

A few happened in class. One in the pool during a swim meet. One in the car while she was driving to school.

"It feels as if someone has my heart in their hand, and they just squeeze it," she said. "And it’s so tight, I just stop moving, and I stop breathing because it hurts."

A spokeswoman for Miami Country Day School would not respond to Caballero's account of her time there, writing in an email: "As an institution, it is not policy to comment on the personal contract between a family and the school."

But Caballero's mom and a classmate backed up her story in detail. Also, she recently detailed her experience in a Facebook post. One of her teachers at the school commented: "As your friend and former advisor, I know that every word you say is true." The teacher did not respond to multiple requests for an interview.

Alexa Randolph, another black student, was Caballero's best friend at Miami Country Day School. She attended from seventh grade through high school, also with a scholarship. Randolph, 22, is set to graduate from Florida State University this summer.

She remembers her friend being "singled out" and bullied incessantly.

"From the minute that she stepped foot on campus at 7:30 in the morning, I would hear the kids speaking to her in ebonics. They would speak to her differently than they would speak to everybody else," Randolph said.

Randolph experienced harassment, too. She remembers reading "Adventures of Huckleberry Finn" in English class and her peers comparing her to the black characters in the book.

Her drama class would do exercises where students would act out the behavior of different animals.

"Mainly the boys, they would do racist things like reenact being an ape, and make it seem like they were reenacting the way that I was behaving or the way that another black kid in our class would behave," Randolph said.

"It definitely made us feel a divide, as if we weren’t their equals," she said.

The two former students both said there was little to no support from adults at the school.

"I never remember a teacher standing up for me, ever," Caballero said.

The bullying got worse for Caballero as she and her peers got older. But she stayed at Miami Country Day School. She said she didn't want to lose the opportunity her scholarship afforded her. She grew up in West Little River, and the public high school she would have attended otherwise had an F-rating at the time.

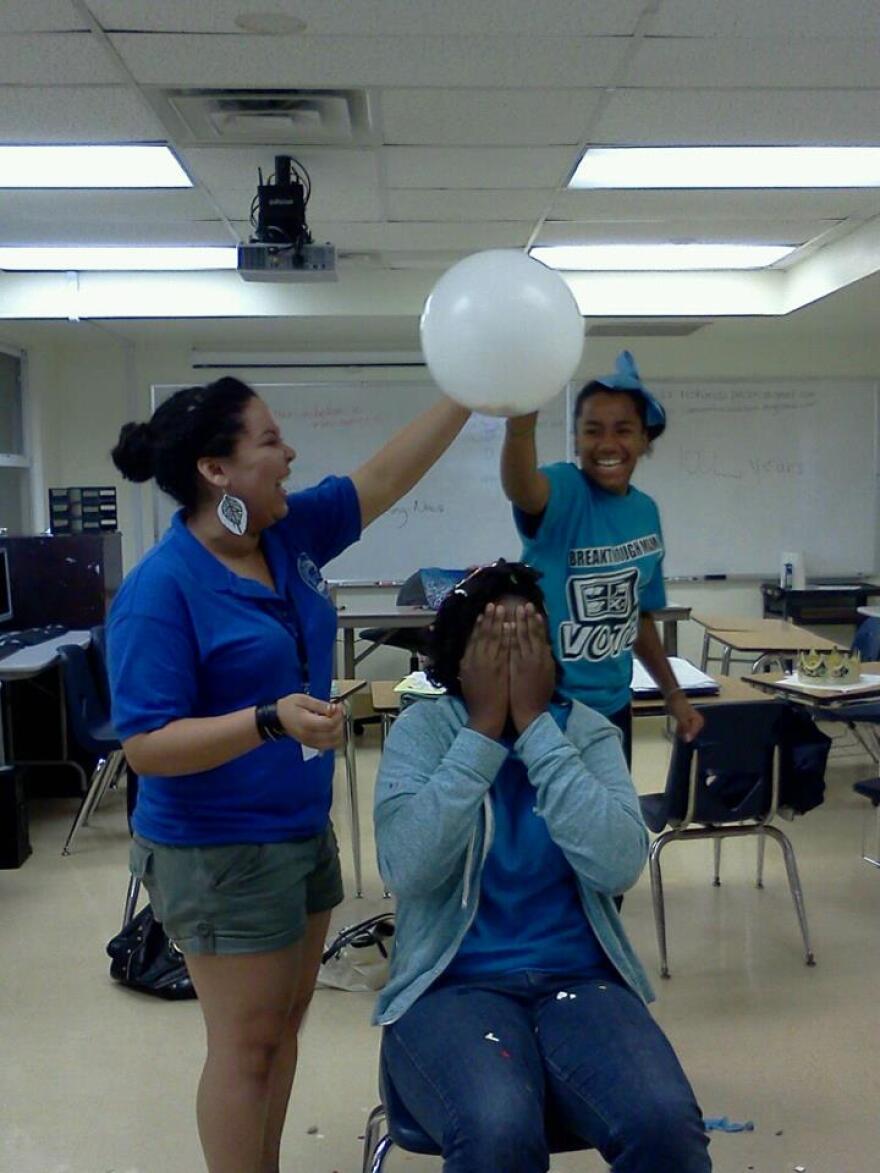

Sophomore year, Caballero gave a presentation to the high school faculty advocating for more events and classroom discussions to recognize Black History Month. An administrator was impressed and offered her a paid internship for the summer of 2012. She accepted, teaching swim lessons, taking pictures for the school's website and working with underprivileged kids as part of a program called Breakthrough Miami, she said.

When school started back up again, she felt connected to the campus, admired by administrators and staff, hopeful. But the harassment from other students continued, and it reopened the wounds she thought had started to heal.

"Coming back from a summer where you feel so respected and working so hard, to going back to the classroom where none of that exists, was such a big transition for me," she said. "The anxiety got really bad."

That's when the panic attacks started up again. Since she was little, she had experienced episodes where her chest would feel tight for a few seconds, and she didn't know why. In 11th grade, it started happening all the time, and lasting for 20 or 30 minutes. Once, an hour and a half.

Her friend Randolph was there for one of the attacks, in history class.

"Her body just froze," Randolph said. "I was very shocked and worried. It was very scary."

Caballero started going to therapy and taking antidepressants. The medication made her feel tired and woozy. One October day, she was sitting in the school library during a free period, and she put her head down on the table.

"I just couldn’t lift it back up," she said. "Like, I’m conscious, but I just couldn’t move."

Someone put her in a wheelchair and took her to the nurse's office. Her mom ended up taking her to Joe DiMaggio Children's Hospital.

"The nurse that assessed me said, 'Do you ever feel like harming yourself?' " Caballero said. "And I told her, 'Yes.' I didn’t want to end my life, but I had thoughts about hurting myself."

She was admitted to the psychiatric unit and stayed for two days.

"She had an air of hopelessness, and I didn't know how to counteract the hopelessness," said Caballero's mom, Colleen Stephens. "It was nothing that my mothering could cure. It was nothing that I could just hold her and kiss her and talk to her, and it would make it better."

After the hospital, Caballero's mom decided she wouldn't go back to Miami Country Day School.

Caballero finished high school by taking a combination of classes online and through dual enrollment in local colleges.

Randolph graduated from Miami Country Day School in 2014 without her best friend.

Reflecting on it now, Randolph said: "I don’t think it’s worth the supposed opportunities that the school gives you to put up with the type of bullying that happens there."

Now Caballero is on track to get her bachelor's degree from Florida International University in December. She said she still struggles with managing anxiety. When she encounters wealthy white people who remind her of her former classmates at Miami Country Day School, she finds it difficult to communicate with them.

"Ten years ago, I felt silenced and I felt powerless," she said. "And I still feel powerless.

"When you experience trauma, trauma is very real," she said. "Especially when it comes to personal trauma, when it comes to who you are as a person. Your identity, your race, your culture. Just you and your humanness. That’s really deep."

A BLACK STUDENT UNION IS BORN

Last fall, Miami Country Day School junior Taylor Lynott started sitting during the national anthem before her volleyball games. The administration noticed.

Lynott was inspired by former NFL quarterback Colin Kaepernick, who sat and kneeled during the anthem as a high-profile protest of police violence against black people in the United States.

"When I was standing during the anthem, I felt like I was disrespecting the black Americans that were killed by police," said Lynott, 17, now a rising senior, who describes herself as "mixed" — her mom is black, and her dad is white. "When I was sitting, I felt that I was speaking up for them."

One of the top coaches met with Lynott and other student-athletes and told them they were expected to stand during the anthem. She was worried she might get in trouble if she protested.

"I remember sitting there — my legs were shaking — thinking, I want to do this so bad," Lynott said. "But, at the same time, I love volleyball. I love playing my sport. I don’t want to have that taken away. I just felt scared."

The then-head of school, Davies, who is white, held an assembly on the topic.

As students filed into the auditorium, a music teacher played a version of the national anthem popularized by Jimi Hendrix. The musician had played it on the electric guitar — with lots of distortion — at Woodstock in 1969 as a protest of the Vietnam War.

It struck Danielle Geathers as ironic.

"For them to play that when they were trying to convince us to conform — that was interesting," said Geathers, 18, a black student who graduated last month.

"My request is — and it’s one rooted in respect, and it’s a request that I make respectfully — that at Miami Country Day School, when the national anthem is played, that we all stand and face the flag," Davies said during the assembly, according to a video Geathers posted on YouTube. "It’s a request. It’s an expectation."

Black students felt like they were being silenced. Geathers challenged Davies in an op-ed in the student newspaper, The Spartacus, writing: "I am disappointed, yet not surprised, that Dr. Davies feels the need to outline his expectations for procedure during the national anthem but hasn’t felt the need to address the oppression of African-American students in his own school."

During a later interview in his office, Davies said he was misunderstood. He acknowledged that other adults reinforced students' perception that protesting could lead to punishment. But he said he intended to communicate that students had a right to protest, even if he preferred that they didn't. He said no students got in trouble for sitting or standing during the anthem.

"I don't believe that you can tell a student that they don't have the right to take a knee during the national anthem, if that's what their heart of hearts and their conscience tells them," he said.

Lynott was co-president of the relatively new Black Student Union last school year. Geathers helped found it when she was a sophomore.

They said the club offers black students a formal opportunity to share their experiences of racism at school with each other.

Like when a few white boys presented a black boy with a surprise on his birthday: a bowl of watermelon. Or when white students in last year's senior class wanted to wear black afros as part of clown costumes during a homecoming event. Or when a rumor spread that a white girl had been romantically involved with a black boy and white students said she had "jungle fever."

Geathers said one of her friends, a white boy, denied to her that "jungle fever" was a racist term.

"If I have to spend 10 minutes trying to explain why 'jungle fever' is racist, am I going to spend my whole life trying to get you to see your own white privilege?" she said. "It’s just defeating. Why try?"

The backlash that followed the assembly about the national anthem was one of a series of clashes the Black Student Union had with administrators during the 2017-18 school year, according to the students.

In February, for Black History Month, the Black Student Union wanted to fly a flag supporting the Black Lives Matter movement. Davies approved it. Black and white with thick lettering that reads, "BLACK LIVES MATTER," the banner was hung below the American flag on a pole in the center of campus.

"The flag was hung for probably about 10 minutes," Geathers said. "The bell rung for class, and as people were walking by, I heard one kid say, ‘Oh my gosh, I can’t eff-ing believe it!' "

A few days later, the flag was gone.

Davies had received complaints — he said he can't remember from whom — that the Black Lives Matter flag couldn't be hung on the same pole as the American flag. The critics had argued it violated the federal flag code, which dictates how the American flag should be presented. (There is some room for interpretation in the code, and at least one faculty member argued the Black Lives Matter flag should be able to stay.)

"The mistake that I made was, … I unilaterally made the decision that the flag could come down," Davies said. "But no communication was made to the students before it came down.

"If I had to do it all over again, there would have been a larger conversation," he said. "It didn't occur to me. My bad."

The students complained: The school flag and class flags have been hung below the American flag for years. Why didn't people complain about the flag code then?

"As I explained to them, I don't know what's in the hearts of the people who suggested it wasn’t with protocol," Davies said. "But my decision was not made on the controversy of the [Black Lives Matter] flag. It was based upon my reading of the protocols."

Miami Country Day School holds an event each June to celebrate graduating seniors. Students are invited to perform.

Geathers and two friends wanted to recite a poem they'd written about racism, sexism and homophobia they said they experienced at school. The other students are 18-year-old white women, one of whom identifies as queer.

The students said two drafts of their poem were rejected. Administrators didn't respond to a request for comment on the incident.

Geathers wore a "Black Lives Matter" T-shirt to the event in protest. One of her friends put on a shirt that said: "Girls Just Wanna Have Fun-ding For Planned Parenthood." Other friends' shirts showed the rainbow flag for LGBT pride or the logo for "March For Our Lives," the national gun-control movement started by Parkland teens after the Feb. 14 shooting at Marjory Stoneman Douglas High School.

Here's an excerpt of the poem, titled "Woke Girl Reflection," by Geathers, Lila Rosendorf and Rachel Thomas:

“We are thankful for many parts of Miami Country Day School./ Nevertheless, we have many problems in our community./ The n-word can be easily heard in our hallways,/ And harmful stereotypes are constantly perpetuated./ Boys in our grade still use homophobic slurs daily./ The understanding of consent is inadequate, and its importance is often ignored./ However, it is the adversity we have faced here at Miami Country Day School that has pushed us into being the women we are today."

Miami Country Day School recent grad Danielle Geathers helped found a Black Student Union, which clashed with administrators throughout her senior year. In June, she and two friends weren’t allowed to perform this poem about being black, queer and/or a girl at their school. pic.twitter.com/Sfk4EoGYkj

— Jessica Bakeman (@jessicabakeman) July 25, 2018

As referenced in the poem, several students and teachers reported that white students at Miami Country Day School use the n-word often, in class and on social media.

Geathers said teachers hear students saying it, but they do nothing.

"So is it my job?" she said. "Like, if they were saying the f-word, … you would silence them. But the n-word? I guess, since it’s controversial, they kind of don’t want to stir anything up."

Educators at the school agreed that some adults there don't feel comfortable calling out students for using the n-word.

Marisol Sardina, a Latina English teacher who sponsors the Black Student Union, said teachers are sometimes hesitant to have conversations with students about race, because, "it's a touchy subject."

"It doesn't come from a bad place," she said. "I just think people are afraid."

Davies, the outgoing head of school, said administrators are "swimming upstream" trying to get students to stop saying the n-word, because they hear it so often in music and movies.

He said he doesn't tolerate the use of the n-word, though, in any form. In making that point, he used the word himself.

"When somebody says, 'You're my n---a' — that, to me, is as offensive as it coming out of the mouth of a Ku Klux Klan person," Davies said. "So I would never hesitate to correct a student."

Black students aren't satisfied with administrators' efforts to combat racism.

"It’s so unclear to them how they are involved in the systemic racism that is oppressing us," said Geathers, who is headed to the Massachusetts Institute of Technology next month. "Nothing will ever change in that school if … their priority is keeping privileged people comfortable."

RACISM AT PRIVATE SCHOOLS 'NOT EXCEEDINGLY RARE'

Miami Country Day School was founded 80 years ago as a boarding school for boys. In the 1970s, the institution began admitting girls and phased out the residential component, turning the rooms where students had slept into classrooms.

Longtime administrators and teachers said the school is more diverse than it has ever been, and they touted the work they've taken on in recent years to make it a more welcoming place.

A few years ago, they brought in a consultant to assess the school's approach to diversifying the student body. Davies, the outgoing head of school, said the consultant commended their efforts to recruit a more diverse pool of students but determined they were struggling to make the school an inclusive environment for everyone.

The student body was about 5 percent black in 2015-16, the most recent year for which federal data is available. The school would not provide newer data. Black students account for closer to 7 percent of private school enrollment nationally, according to the National Association of Independent Schools (NAIS).

Miami Country Day School's population of Hispanic students, though, is much higher than peer schools nationwide. Miami residents are mostly Hispanic.

Tuition at the school starts at $22,500 for kindergarten, and goes up to about $35,000 for high school. Eighteen percent of students receive financial aid.

The diversity consultant, Keno Sadler, conducted the review during the 2012-13 and 2013-14 school years, according to a parent who was interviewed as part of the process. He later produced an audit with recommendations, which Davies said he used to inform a new strategic plan for the school.

Reached by phone, Sadler said he could not share any information about his assessment of the school. Davies' office would not provide a copy of the audit or the strategic plan. A spokeswoman said the documents were confidential.

Davies and two teachers who agreed to an interview with WLRN highlighted faculty members' and students' participation in several national conferences focused on diversity and inclusivity. Also, administrators have helped organize student-led discussions, including some focused on racism. For example, there's an increasingly popular lunchtime event called "pizza with a point."

"These are discussions that are so important to have, but they're messy," Davies said. "Courageous conversations are conversations that are uncomfortable, they're difficult and sometimes painful. But that's the only way that we can move forward."

National experts said black students' experiences at Miami Country Day School mirror that of their peers at predominantly white private schools around the U.S.

"The experience that you’re describing is unfortunately not exceedingly rare," said Myra McGovern, vice president of media for NAIS.

Experts said it has gotten worse since President Donald Trump's election, which has intensified racial tensions and amplified the polarized nature of the country.

"My client base has increased exponentially since the 2016 election," said Batiste, the Houston-based consultant who works with private schools on diversity and inclusion. Several of his client schools have come to him to help with incidents where students used racial slurs or other derogatory language on social media.

Adults are often the barriers to making improvements, he said.

"We are preparing students for their future, not our past," he said. "And so often, we, the adults in the school, bring our own baggage from our own experiences, either professionally or personally."

It takes strong leadership to make schools more tolerant places, said Peter Kuriloff, a counseling psychologist and professor at the University of Pennsylvania's graduate school of education.

For the last 15 years, Kuriloff has studied students' experiences at 10 elite private schools, including Phillips Exeter Academy in New Hampshire and Miss Porter's School in Connecticut.

What administrators and teachers should do, he said, is "start listening to kids very carefully, and put them to work explaining to us — who tend to be pretty ignorant — what it’s like in their skin," he said. "And then to figure out together what would help."

This story was updated to include the years when consultant Keno Sadler conducted a diversity audit at the school.