The first major assessment of coral near busy Port Everglades in a decade has led scientists to a surprising discovery: one of the world’s busiest channels is also home to millions of corals, including what may be the largest stand of wild staghorn left on Florida's reef.

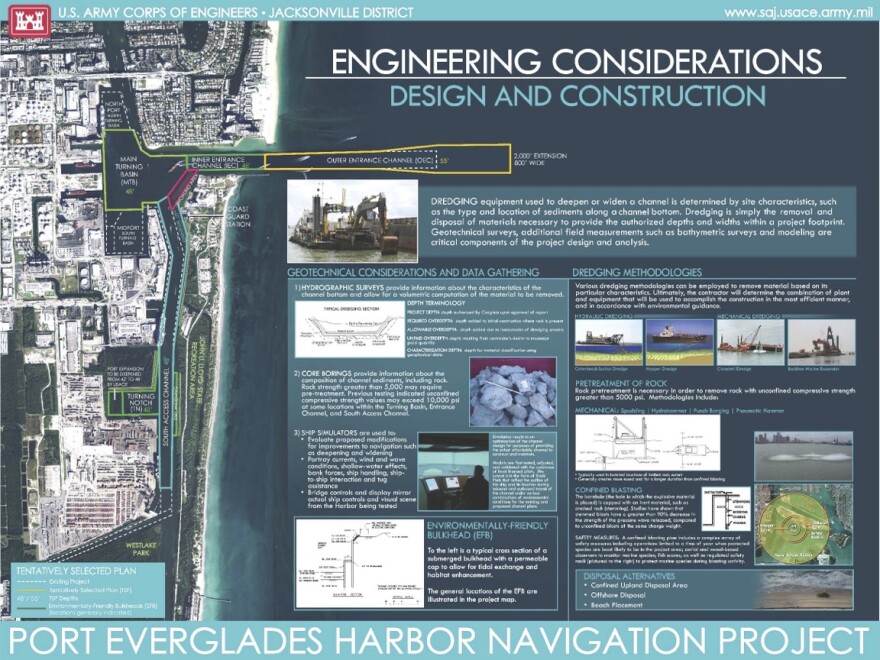

The findings come as the U.S. Army Corps of Engineers prepares to scoop up more than 6 million cubic yards of ocean bottom to deepen the port.

In their report, scientists warn the work could kill the coral, mirroring damage done a decade ago at the PortMiami dredge. One of only two known herds or rare, breeding Queen conchs that live near the port are also at risk. The amount of coral lost, scientists estimate, would far exceed the capacity of labs and nurseries breeding coral for restoration work.

So few staghorn and elkhorn coral remain on the reef, according to another study published Thursday in the journal Science , that scientists now consider them functionally extinct and unable to play a part on Florida's reef. Scientists use the designation for wild species about to disappear entirely.

READ MORE: A 'catastrophe' in the Lower Keys: Summer heatwave wipes out iconic elkhorn coral

”There are over 10 million corals just within 1.2 kilometers (about 300 acres) of the channel at Port Everglades,” said Ross Cunning, the study’s lead author who worked with two scientists from the National Marines Fisheries Service. “We can't afford to lose these corals and expect that we can just restore these reefs back, because it's just not possible.”

In response to WLRN requests for comment, Army Corps officials wrote in an email that federal officials were unavailable because of the government shutdown.

Over the years, South Florida’s 350-mile long reef — the only barrier reef in the continental U.S. and a powerful protector from storm waves — has been hit hard by rising temperatures and disease. Stony coral disease, which spread after the PortMiami dredge, led to bacterial infections that attacked reef-building boulder corals, while bleaching events from rising temperatures have decimated branching staghorn and elkhorn coral. The last wild stands of elkhorn in the Lower Keys were killed by a record-breaking heatwave two summers ago. Scientists now believe the tract is shrinking faster than it’s growing.

And as the Science study warns, without intervention, two of the most critical coral needed to build reefs, will be lost without more restoration work.

"Aggressive interventions are necessary at this point," Katey Lesneski, the research coordinator for the Florida Keys National Marine Sanctuary's Mission Iconic Reef project said in a statement.

That could mean cross-breeding Florida's coral with those from warmer waters, a project already underway, or looking for more heat-tolerant algae species that coral need to survive, she said. That also means that the remaining wild staghorn and elkhorn become critical to maintaining genetic diversity and avoiding complete extinction, Cunning said.

At least five surveys have been done at the port over the last 15 years, but they focused on coral protected under the Endangered Species Act or those within the footprint of the planned dredge, and occurred during the ongoing disease and bleaching.

“So it's been very difficult to get a sort of up-to-date assessment of how many corals are out there,” Cunning said.

Given the dire conditions elsewhere, Cunning said the team expected to find coral in similar distress. But their analysis revealed a surprising change in coral near the port — a nearly 70% increase in density in coral since 2017. That was due mostly to an increase in hardy starlet coral that grow in boulder-shaped colonies, weedy finger coral and mountainous star coral.

The team also found what they estimate could be the largest remaining stand of wild staghorn coral on the tract, a ranking that may be partly due to its location. The blistering heat from the 2023 marine heat wave remained largely in the Keys and spared the northern end of the reef that extends to Martin County. Another unexpected find: coral in the port appear to be recovering from stony coral disease. More young coral were also found than in other places.

”They really are functioning as good coral reef habitat,” Cunning said.

But figuring out why will take more research and could become part of wider effort looking at urban coral to understand how some survive, and even flourish, in places like busy ports where pollution, ship traffic and swift currents create conditions that might otherwise seem inhospitable.

“ I'm not sure we can say with much confidence that Port Everglades is a magical hotspot,” he said.” But it's certainly not a bad area.”

For activists hoping to save the coral, the findings provide further proof that the Corps should heed the lessons learned from the PortMiami dredge. The Corps initially estimated only about seven acres of coral would be harmed near Miami’s harbor. But the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration later confirmed dredge work killed coral across 278 acres.

About 10,000 coral were later planted to restore damage to settle a 2014 lawsuit filed by Miami Waterkeeper for failing to protect the coral. But Waterkeeper executive director Rachel Silverstein said the work covered just a fraction of the damage.

”Ultimately the millions of corals that were killed and the 278 acres of reef that was damaged in Miami has never been fixed,” she said, even though Miami-Dade County agreed to pay the cost of the restoration work.

“It’s still a big gaping wound for Miami,” she said. “We lost this huge area of reef that was protecting our coastlines from storm surge, supporting fish and other habitats, supporting ecotourism and diving, and just incredible amounts of biodiversity right in our backyard. It’s gone and buried and is probably not coming back on its own given the state of reefs.”

Waterkeeper also sued the Corps to improve dredge operations at Port Everglades, where NOAA characterized the project as “the largest permitted coral damage ever in the history of the United States,” Silverstein said.

The Corps initially agreed to reconsider the work to avoid some of the techniques used at PortMiami, she said. But in January, Corps officials began rushing to complete the project, she said, submitting a required biological assessment to NOAA that dropped some of the protective measures due to costs and instead relied on moving coral rather than avoiding damage to the reef. The plan is now open for public comment through Oct. 31.

“I was very surprised by this report,” Silverstein said of the findings by Cunning and NMFS scientists. “There is something special about this area that we don't yet understand. It is very much worthy of our protection and our research interest and taking every single possible hard look at this project to understand is it even still necessary.”

This story was updated to clarify that Miami-Dade County agreed to pay for coral restoration near PortMiami. It was not required under state law.