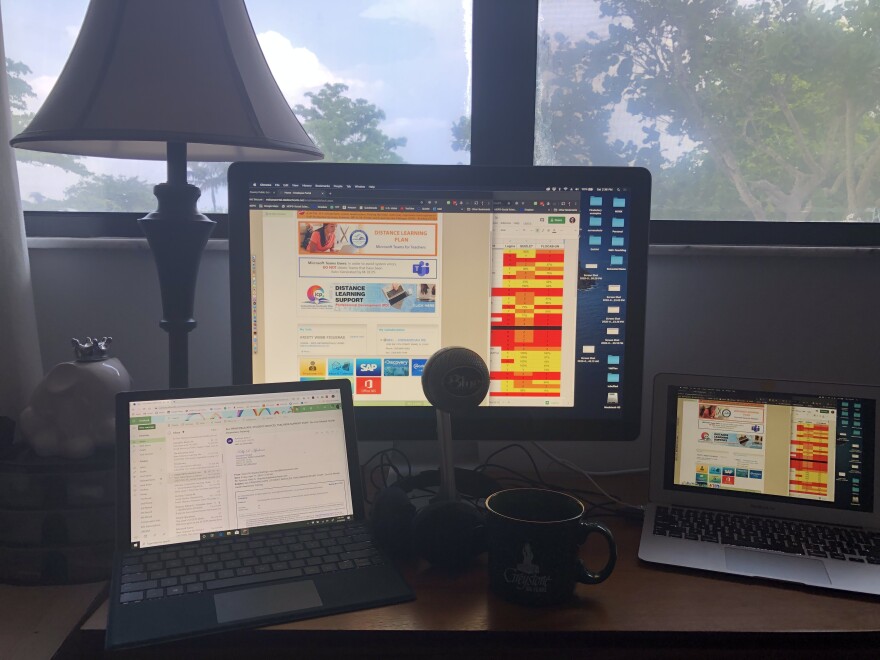

Shenandoah Middle School teacher Kristy Figueras uses a color-coded spreadsheet to keep track of her students.

Yellow is for the kids who show up for virtual learning every day and are consistently completing assignments. Orange is for those who have logged on but aren’t doing their work. Red is for the ones who’ve disappeared.

WLRN is committed to providing South Florida with trusted news and information. In these uncertain times, our mission is more vital than ever. Your support makes it possible. Please donate today. Thank you.

“I am trying to get a little less red and a little more yellow, and I’m trying to turn the oranges into yellows," Figueras said.

“I’d like to get everybody off the red, but I know that’s probably not going to happen, no matter what I do,” she said.

Figueras teaches social studies and special education to 97 students at the middle school in Little Havana. Like all public schools in Florida, hers will be closed through the end of the academic year in an ongoing effort to slow the spread of the coronavirus.

Her experience highlights a difficult truth of this unprecedented experiment: Distance learning is a lot harder for some families than others, and the students who were already struggling are likely to fall even further behind.

Despite the best efforts of school districts, virtual learning exacerbates the existing inequities in education. That’s true in Miami-Dade County, where early data show the schools with the lowest attendance rates serve big populations of students who are living in poverty or still learning English.

“In the midst of this pandemic, we see the manifestation of the pandemic of poverty,” said Steve Gallon III, vice chair of the Miami-Dade County School Board. “When things get bad for communities, … sadly and unfortunately, things get worse for our children and our families living in poverty.”

Still, the district has seen attendance numbers climb as administrators have employed a variety of strategies to get students logged on and engaged, including sending staff to knock on doors. Overall, attendance is now around 92 percent.

“It's a terrific movement in the right direction,” Superintendent Alberto Carvalho said. “With that said, we continue to intensify our efforts.”

Low-income families often have less bandwidth for virtual learning

Twenty-nine Miami-Dade public schools recorded average attendance rates below 80% for the first two weeks of April, according to a WLRN analysis of school district data. An average of 92% of students at those schools are considered economically disadvantaged, according to the state Department of Education. District-wide, about 68% of students are in that category.

The central region of Miami-Dade is home to about a third of the district’s public schools but 70% of those with distance learning attendance rates lower than 80%. That includes schools in some of the county’s poorest neighborhoods, such as Allapattah, Brownsville, Liberty City, Little Haiti and Overtown.

One explanation of why poorer families are having a harder time participating in distance learning is fairly simple: Many low-wage workers like grocery store cashiers and delivery people are considered “essential” right now, so they’re still working outside their homes. If parents are working, it’s harder for them to help their kids with school work.

And as the economy sputters, some low-income families are more worried about feeding their kids than educating them.

“There's the economic uncertainty: Can I pay my bills? Will we eat?” said Pedro Noguera, an education professor at the University of California, Los Angeles. “Basic needs are in jeopardy and in doubt for many families, especially the undocumented. And so that is a huge stress that's going to certainly be a distraction away from learning.”

Another explanation is the so-called “digital divide.”

Miami-Dade County Public Schools has distributed more than 105,000 laptops, tablets and smartphones to students who needed them. Some of the smartphones are being used as wifi hotspots. The district also worked with internet service providers to establish free or low-cost options for families of school kids.

Those distributions continue as the district identifies more students who are lacking.

Principals “have made literally hundreds of appointments daily with families to equip them with devices and hotspots for connectivity,” Carvalho said. “We've been running about six- to seven-hundred daily appointments for the handing off of devices and connectivity.”

Carvalho personally visited Jones Fishing Camp, a mobile home park in Hialeah where 66 public school students live. The visit was mainly for distributing hot meals, but administrators also handed out 40 devices in that one trip, he said.

About 99% of the district’s students have logged on to the online education portal at some point, giving administrators confidence that the vast majority have access to the technology they need to connect.

Some families are sharing devices among multiple children, though. That means, in some cases, a child might miss out on virtual education so a sibling can participate.

Families who can afford to purchase multiple devices don’t have to make those choices.

In families with more resources, “everybody in the house has them — a phone and a tablet and a laptop. They have the technology. Our children don't have that,” said Catherine McKham, a third-grade teacher at Laura C. Saunders Elementary School in Homestead where 97% of students are in poverty. The school had an average 69% attendance rate for the first two weeks of April.

Getting a device and internet connectivity is only half the battle. Then there’s learning how to log on and interact with the virtual education programs, which some teachers say are not user-friendly. That’s even harder for kids who have not had access to technology at home and therefore have less experience using it.

Figueras, the Shenandoah Middle School teacher, said many of her students don’t know how to do relatively simple online tasks like checking email. She’s especially worried about her sixth graders.

“These are kids who just went through the tough change of leaving elementary school. They had a hard time just keeping the schedule of different classes and different teachers, let alone emails and logins and passwords,” she said.

Megan Gabelman, a third grade teacher at Santa Clara Elementary School in Allapattah, said she has dealt with parents who felt overwhelmed and were ready to give up on the technology. In one instance, she had a Zoom call with a mother and daughter to show them how to click on a hyperlink and open a new tab.

About 94% of students enrolled at Santa Clara live in poverty. The school is averaging about 83% attendance.

“We assume if we give a child a laptop, then they're good to go,” Gabelman said. “There is a digital literacy gap. If we are now employing online distance learning, we know that that is going to be a barrier.”

‘They’re fearful’: Deportation worries, language barriers stall online learning for some immigrant families

Schools that serve large populations of immigrant students are also struggling under the new normal. A cluster of five schools with low attendance are located in Homestead, an agricultural area in the southern part of Miami-Dade County where many families of migrant farm workers live.

On average at those five schools, 31% of students are still learning English. At one of them, West Homestead K-8 Center, nearly 57% of students are English language learners. The district average is about 19%.

Some of those schools serve undocumented families from Guatemala who do not speak English or Spanish. They speak Mayan languages like Mam. So it’s harder for school district staff to communicate with them.

And some families are afraid to reach out for help because they worry they could attract attention from immigration authorities.

“They're fearful,” said School Board member Lawrence Feldman, who represents south Miami-Dade County. “There are a lot of kids who have immigration fragility, or very fragile statuses, and are very worried.”

McKham, the third-grade teacher at Saunders Elementary in Homestead, said just getting her students to log on for attendance is a cause for celebration. About 30% of the school’s more than 600 students are English language learners.

She has 46 students in her math, science and social studies classes, and she estimates only about a dozen are completing assignments regularly.

“I weep almost every day, because they’re my babies. I love them,” McKham said. “And to not be able to find them, and to not be able to at least see that they logged in, that they’re OK ….” She trailed off.

“I know I’m making a difference, but I don’t feel like I’m making a difference — not as much as I would be if I was right there with them,” she said. “They can’t feel the love that I have for them. I can’t hug them if they’re upset. … We can’t have those heart-to-heart conversations, because we’re not together.”

What the numbers do — and don’t — tell us

The available attendance data don’t offer a perfect picture of distance learning in Miami-Dade County.

Attendance might be higher than the initial data show, because students and their families have 72 hours to appeal absences and offer evidence of participation, like a completed assignment or an email exchanged with a teacher. Not all of the data obtained by WLRN reflects corrections made as a result of those appeals.

An important piece of context explaining why some poorer schools have lower attendance rates: The data are skewed by low attendance among pre-kindergarteners.

Because pre-K for poor children is federally subsidized with Title I funding, elementary schools in impoverished neighborhoods are more likely to have pre-K programs. Unlike kindergarten, pre-K is voluntary. And the youngest students can be the most difficult to get engaged in virtual learning, because it’s harder to hold their attention for long periods of time and they require more assistance from parents than older students.

“They're probably the most difficult kids to sit in front of a computer,” said Carvalho, the district superintendent. “That's not necessarily what we do at school. A great pre-K class is highly interactive, highly sociable.”

For example, about a third of the student body at Melrose Elementary School in Allapattah is in pre-K. When the school’s more than 200 pre-K students are included, it has the lowest attendance average in the district: under 60%. Without pre-K students, attendance is around 90%.

Further, attendance numbers don’t necessarily reflect participation. If students log on once during the day, they are considered “present.” That doesn’t mean they’re learning.

Some teachers are frustrated by the district’s attendance numbers, which they argue are not an accurate reflection of students’ learning.

“The whole concept of, they log on to the portal and they’re counted for attendance, … it’s like showing up at the door, being like ‘I’m here,’ and then leaving,” said Kristy Figueras, the Shenandoah Middle School teacher.

While her school is seeing attendance rates around 93%, she said most of her students aren’t consistently participating.

“I understand the district needs to take attendance,” Figueras said. “We need to know who’s completely lost out there. … But what can we do when the kid logs on the portal and then logs off?”

Megan Gabelman, the third-grade teacher at Santa Clara Elementary School, said only about half of her 42 students are consistently doing work online.

“For me, it’s very concerning,” Gabelman said. “If students are simply expected to clock in, I think it sends a message to families and to students that it's okay that your child's not learning.”

School district uses data to target students who are offline

The Miami-Dade school district is using attendance data to determine which students still need to receive devices or other assistance in getting logged on.

District staff have been conducting home visits and wellness checks for students who have not been in touch with their teachers. The visits are typically done by community involvement specialists, staff members who work at schools and therefore are known to students.

“Sometimes it is detective work,” Carvalho said. “For some of our most transient parents, they have moved. For those same parents, some have had their phones disconnected, their mobile phone disconnected.”

The staff members conducting the visits wear masks, gloves and are sometimes escorted by police officers. Carvalho said police are very rarely the ones knocking on doors themselves, because uniformed authorities might spook families, especially those who are undocumented.

As more students are reached and begin virtual learning, teachers describe the exhilaration of watching their attendance numbers tick up.

Peggy Slott teaches at Ruth Owens Krusé Education Center, a small specialized school in Kendall that serves students with disabilities.

The school’s numbers started low, but she said as more students got devices and learned how to engage, attendance shot up. The school's attendance rate was in the high 80s at the end of last week.

“I don’t have a single student that’s not in class every day at this point. I’ve got them all,” Slott said. She teaches six intellectually disabled 12th graders who range in age up to 22 years old. One of her students lives in a group home and receives help from the home’s staff to participate in virtual education.

“This is not how I would want to teach,” Slott said, “but, for now, we’re all doing our very best.”