The driver makes sure Malik is wearing a face covering when he boards the bus. He arrives at school at about 7:35 a.m., and before he can pick up his breakfast in the cafeteria, he washes his hands. When he arrives in homeroom, he’s with only about a dozen other children, their desks spaced six feet apart.

Broward County Public Schools administrator Valerie Wanza walked the school board through a day in the life of this fictional fourth grader, as the nation’s sixth largest school district prepares to reopen amid a raging pandemic.

WLRN is committed to providing South Florida with trusted news and information. In these uncertain times, our mission is more vital than ever. Your support makes it possible. Please donate today. Thank you.

"We are not taking temperatures, because we are relying on the parent to ensure that Malik is healthy to attend school for the day,” Wanza told the board during a virtual meeting on Monday morning.

Under the district’s current plan, students would be learning in school about half the time and online, at home, for the other half, alternating days to keep school campuses at 50 percent capacity.

Half the time isn’t enough for Adam Herman, a parent who offered his own fictional account during public testimony. He focused on Malik’s day at home, not at school.

“Perhaps Malik is home alone because his parent or parents have no other option,” Herman said. “So while Malik helps himself to some Cool Ranch Doritos and some Twinkies instead of his normal healthy school meal, does Malik accidentally set the house on fire?"

Herman is among the third of Broward County parents who want their kids back in school full time, five days a week, starting next month.

The state and federal government want to make that a reality. On the same day President Donald Trump tweeted, “SCHOOLS MUST OPEN IN THE FALL!!!,” the Florida Department of Education announced a similar mandate for school districts in the state, even as the number of coronavirus infections and hospitalizations continues to skyrocket.

“All school boards and charter school governing boards must open brick and mortar schools at least five days per week for all students, subject to advice and orders of the Florida Department of Health, local departments of health” and Republican Gov. Ron DeSantis’ executive orders, according to the edict signed Monday night by the state education commissioner.

While the Florida Constitution expressly assigns authority over public education to locally elected school boards, state officials control the money. And now they’re making some funding — as well as crucial waivers from strict laws that would be difficult to adhere to during a pandemic — contingent on their approval of districts’ reopening plans.

“The levers that the department can pull with regard to flexibilities and funding is where they're putting the requirement to submit a plan,” said Andrea Messina, executive director of the Florida School Boards Association. “So if you want them to pull one of the levers, … you're going to have to comply with this expectation.”

South Florida school district leaders have asserted their local authority.

"It is up to each individual school district how it opens in the fall,” Broward County superintendent Robert Runcie said during the school board meeting Monday. “We will continue to follow the advice of our local public health and medical experts as to how and when it is safe … to return to school.”

Can the state force schools to reopen?

The message was clear during a webinar for school district leaders Monday afternoon: “All schools need to be open,” said Jacob Oliva, a top official at the DeSantis administration’s Department of Education.

Still, districts would be able to grant families’ requests for part-time or full-time online learning — with state approval.

The mandate for in-person classes could also be overridden by health department officials, according to the education commissioner’s executive order. The significance of that caveat is unclear, though, since DeSantis exercises tight control over public health officials at the state and local levels.

“There may be some challenges with local health departments and the Department of Health and executive orders into making that happen,” Oliva said, referring to a full reopening of schools. “We stand ready to work with districts to help meet those challenges.”

Oliva was speaking on behalf of his boss, education commissioner Richard Corcoran, the conservative former speaker of the Florida House of Representatives. He was the governor’s pick to lead the department — and the DeSantis administration is now in lockstep with Trump and U.S. education secretary Betsy DeVos, who’ve made it clear they want kids in classrooms come fall.

Trump has even threatened to withhold federal funding from districts that refuse. The Florida Department of Education is also making some funding contingent on state approval of districts’ reopening plans.

If districts get state sign off, they will receive per-student funding based on pre-pandemic student headcounts. In other words, they’ll be held harmless financially if enrollment drops because of COVID-19.

The department is also offering waivers from certain state laws that could be impossible to comply with because of the fluid nature of the pandemic — like the requirement that students must spend a certain amount of time physically in classrooms. Districts will get those waivers only if the state accepts their plans.

Florida's state teachers' union has called the education department's move political, but state leaders say it's about giving parents choices.

“That is something that we have definitely heard consistently, loud and clear — that there are a lot of families that want their children to come back to school,” Oliva said. “And we want districts to be able to provide that option.”

South Florida school districts’ plans haven’t changed

South Florida school district superintendents aren’t necessarily going along with state officials’ directives.

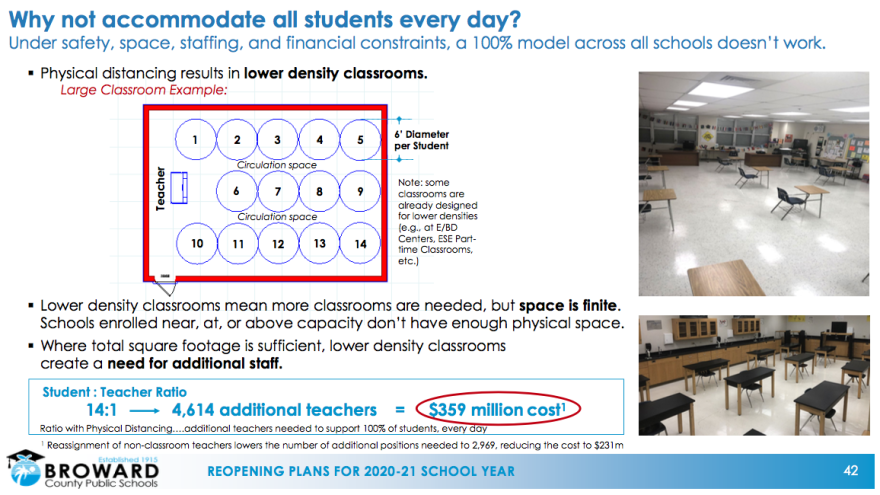

“One thing is clear at this time: We do not see a realistic path to opening all district schools with 100 percent full enrollment every day,” Runcie, the Broward superintendent, said during Monday’s school board meeting.

Initially, Miami-Dade County Public Schools superintendent Alberto Carvalho tweeted a statement calling the state's new guidelines "fair and measured" and contending that they were consistent with the district’s current plan. He expects to offer a full-time in-person option for families who choose it, along with a fully online model and a combination of both.

Read More: MDCPS Approves Reopening Plan — Here's What Parents Should Expect

He later clarified the coronavirus spread is too out of control in South Florida now to consider reopening.

"I will not reopen our school system August 24 if the conditions are what they are today,” Carvalho said Tuesday during an appearance on CNN.

Carvalho said the district will bring students back into school buildings when the county enters phase two of its own reopening plan. Now, Miami-Dade is in phase one, and officials have started reversing course on loosening restrictions on individuals and businesses.

If and when that reopening day comes, though, Carvalho said schools would take all the necessary precautions to shield students and staff: “social distancing, with the wearing of [personal protective equipment], with visors and dividers and masks,” he said on CNN.

Parents, teachers weigh risks and benefits of reopening

Adam Herman, one of the Broward parents who has opposed the district’s plan to keep students home at least some of the time, said the spring’s school closures were “a disaster” for his three daughters. His oldest essentially taught herself five chapters of chemistry, he said.

For his family, he said the risks of not reopening outweigh those of going back to school.

"I am infinitely more concerned about the mental health aspects and emotional aspects and the social aspects than I am about the exposure to COVID for my children,” Herman said.

While it is rare, three children in Florida have died of COVID-19.

That’s Sandra Almeida’s nightmare. She teaches at an elementary school in Little Havana, a hard-hit neighborhood where local officials recently sent “surge teams” to combat the virus’ spread by handing out information and supplies.

"If a student in my care were to fall sick and — God forbid — even die, I don't know how I would deal with the guilt,” Almeida said. “I would feel like: ‘Did I not clean a surface? Did I not keep them far enough apart?’

“The guilt could kill me."

Almeida said the district's plans to protect students and staff — like requiring masks and social distancing — are well intended but impractical.

She drove to each of her kindergartners’ homes earlier this summer to deliver their diplomas, handing them out safely from her vehicle, “and they were trying to hug me through the car window,” she said.

"They are so starved for that physical contact," she said. "For me, it makes it even more unrealistic for them to return next month and for us to be like, ‘Hold it! No hugs!’”

“I teach the babies,” she said. “How do I console a crying child from six feet away?”

Almeida is not just worried about her students’ safety but that of her family. If she got the coronavirus at work, she could give it to her 85-year-old father or her asthmatic mother. Forced to return to her classroom, she would have to stop visiting her parents and find someone else to care for them.

Jennifer Barreto is worried about her own health. The MAST Academy Homestead science teacher said she has an underlying medical condition and blood type that researchers have found could make her more vulnerable to severe illness from COVID-19.

She said she’d leave her job if she was told she must teach in person.

“This is the place I love to teach. I love my students. I love the people I work with. I don't want to change that,” she said. “But I'm also not going to risk my life for that.”