The rain that pounded South Florida last week, and dumped a half foot on Miami International Airport in just two hours, also tested the limits of the old Tamiami Canal.

As water backed up across the network of canals that rely mostly on gravity to drain to the coast, the canal rose more than a foot along a seven-mile stretch that runs from the Miccosukee Indian Reservation to the Miami River, said Armando Vilaboy, who represents Miami-Dade and Monroe counties for the South Florida Water Management District.

WLRN is committed to providing South Florida with trusted news and information. In these uncertain times, our mission is more vital than ever. Your support makes it possible. Please donate today. Thank you.

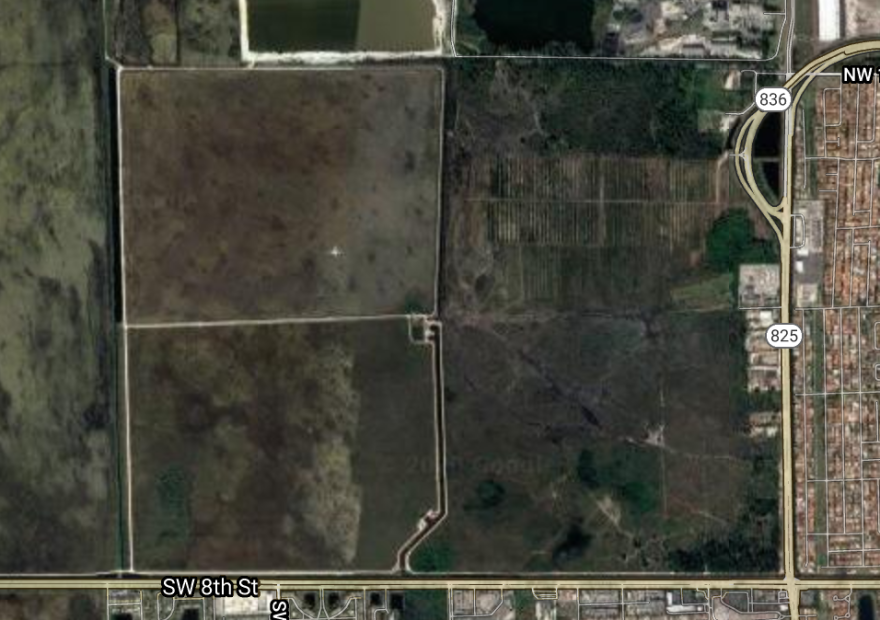

That prompted the district to start pumping into an emergency drainage basin just east of the reservation and the size of about 600 football fields.

“Think of it as the water management system’s elephant gun,” he said. “You have one shot and once you use it, it’s full.”

The basin can hold up to a billion gallons of water and works as a back-up to the canal, also known as the C-4, that helps provide flood control for about 600,000 people. A day after the rain stopped, Vilaboy said the basin was half full and as full as it’s ever been.

“There's normally no water in there. And if you go now it's full of water,” he said.

The basin was a part of a $70 million flood control project built by the district — and mostly paid for with Federal Emergency Management Agency money — after the No Name Storm flooded more than 90,000 homes in Miami-Dade and destroyed more than a thousand in 2000. The storm hit just a year after Hurricane Irene flooded the area with nearly a foot of rain around the airport.

In addition to the basin, the project cleaned up banks along the canal that was dredged in the 1920s to help build the Tamiami Trail. Over the years, the canal that winds through neighborhoods and urban areas had become cluttered with makeshift docks, utility sheds and overgrown trees.

“There were a lot of things there that were very interesting, to say the least,” Vilaboy said. “Before that bank project, a neighbor could have two feet [of elevation] and another neighbor could be at eight feet. So the section [that's] two feet would let water creep in a neighbor's yard and flood out the neighborhood. Now it's uniform.”

In advance of the rain, the district had begun lowering water in the C-4 and other canals, although he said many were already low because of the winter drought. The canals, along with local drainage systems, mostly controlled flooding over the weekend and even Tuesday morning outside of chronically flood-prone low areas.

But as the rain persisted, it backed up, even in areas like Coral Gables that sit on high ground.

A National Weather Service gauge just over two miles away, on the canal just west of the Palmetto Expressway, recorded a two-foot rise in three and a half hours Tuesday afternoon, said warning coordination meteorologist Robert Molleda.

"Obviously that much rain in a short amount of time is virtually impossible to contain from a water management perspective and it's just a matter of how long it lasts which determines whether it can lead to problems," he wrote in an email.

The heavy rain left the Granada Golf Course underwater and flooded some streets with nearly a foot of water.

“Certain communities like Sweetwater saw impacts very fast and very furious,” Vilaboy said. "It was even very high where I live in a high area of Miami-Dade County. We've never even seen flooding, even in some of the hurricanes."

Part of the flood improvement project also replaced old gates that rely on gravity to move water to the coast with two pump stations near Miami International Airport. The pumps have been touted as a fix to rising sea levels that make the gates less efficient since the gates can only open at low tide. The district operates about 36 coastal pumps. District engineers have warned that as seas rise, they will need to replace 26 at a cost so far estimated at about $700 million.

During the worst of the flooding, Vilaboy said the pumps operated nonstop. Coastal cities like Miami and Miami Beach have also begun installing their own pumps to deal with tidal flooding.

But Vilaboy said the surrounding network of storm drains and local canals compounded the flooding because some older storm drains are too small to handle the amount of rain that fell. Local canals also need to be cleaned and maintained, he said.

“The South Florida Water Management District moves bulk water. But the secondary system, which is managed by the county, and the tertiary system, which is managed facilities, also have to move that water,” he said. “If that water doesn't get to the district canal system, we can't move it.”

Over the weekend, he said district officials met with local drainage workers to address hot spots. Some low areas in Miami and Sweetwater may also have to rely on mobile pumps if heavy rain persists during the upcoming hurricane season. The district may also try to manage the C-4 at a lower level, he said, by amending an operating plan it has with Miami-Dade County, Miami, West Miami and Sweetwater.

This story was updated with additional information from the Miami Office of the National Weather Service.