Roy Black, a nationally prominent defense lawyer who successfully defended William Kennedy Smith in his 1991 trial for rape and helped Jeffrey Epstein secure a plea deal in 2008 that enabled him to escape federal sex-trafficking charges, died Monday at his home in Coral Gables, Florida. He was 80.

His law partner Howard Srebnick confirmed the death without specifying the cause, saying only that Black had dealt with a “serious illness.”

Black defended the notorious and the obscure, celebrities and sports stars. His clients included Justin Bieber and Rush Limbaugh, as well as Florida police officers accused of misconduct. He usually emerged victorious from his courtroom battles.

But it was the acquittal he won for Smith — a 30-year-old nephew of President John F. Kennedy and Sens. Robert F. and Edward M. Kennedy — that gave Black a national profile, in a case that tested the outer limits of power and influence.

The trial pitted the word of an accuser — later identified in the news media, including by The New York Times, as Patricia Bowman, whom Smith had met at a local bar — against the word of a member of one of America’s most powerful families.

Black made full use of the disjunction between accuser and accused, eliciting emotional testimony from Edward Kennedy and from his nephew.

In the end, the jury took 77 minutes to acquit Smith. The judge, Mary Lupo, had refused to allow evidence of previous accusations of sexual assault against Smith, a decision widely seen as a major boost for the defense. Writing about the case in Vanity Fair in 1992, Dominick Dunne noted that Lupo had been photographed greeting a Kennedy in-law, R. Sargent Shriver, in the courtroom; she had been introduced to him by Black.

Seventeen years later, Black was part of the legal team that secured a controversial plea deal for Epstein that was signed off on by Alex Acosta, the U.S. attorney for the Southern District of Florida at the time. (He later became the secretary of labor in the first Trump administration.) Epstein had been under federal investigation, accused of sex-trafficking teenage girls.

Under the deal, federal prosecutors agreed not to pursue sex-trafficking charges in exchange for his pleading guilty to two prostitution charges in state court. Epstein was sentenced to serve just 13 months in the county jail with a work-release stipulation, allowing him to spend 12 hours a day in his Palm Beach, Florida, office.

“He had a chauffeur picking him up at the Palm Beach jail every morning, and they didn’t return him to the jail until 10 o’clock at night, so he essentially only slept there,” said Julie K. Brown, a reporter for The Miami Herald who had exposed much of the Epstein case, in an interview with the Times.

Black was part of a so-called Dream Team of lawyers representing Epstein; others included Alan Dershowitz, who later helped represent President Donald Trump in his second impeachment trial, and Kenneth Starr, the independent counsel whose investigation led to President Bill Clinton’s impeachment in the 1990s.

“Roy was selected by this group of attorneys because he was the absolute titan of the Southern District” of Florida bar, Martin Weinberg, another lawyer on the Epstein team, said in an interview. “He would have been Epstein’s choice to be his chief trial lawyer if he had been federally indicted.” Epstein would not be under federal indictment for 11 more years, when New York prosecutors brought charges shortly before he was found dead in his cell in Manhattan’s Metropolitan Correctional Center in 2019, in what was ruled a suicide.

Roy Eric Black was born Feb. 17, 1945, in the Forest Hills neighborhood of Queens, New York. His mother, Minna, divorced his father shortly after his birth and married an executive with Jaguar automobiles, Michael Bennet, who moved the family to Jamaica when Roy was 15.

He attended Jamaica College, a secondary school in Kingston, and earned a bachelor’s degree from the University of Miami in 1967 and a law degree from its law school in 1970.

Black worked for the public defender’s office in Miami for several years before opening his own practice.

He came to local prominence in 1984 with his successful defense of Luis Alvarez, a Miami police officer who shot and killed a young Black man, sparking several days of rioting in 1982.

“Most of the city’s leaders thought there was only one way to get rid of the problem: Blame Luiz Alvarez,” Black wrote in his 1999 memoir, “Black’s Law.” “I remember thinking that if this cop thought the shootout was bad, just wait for the backlash from an establishment desperate to keep racial peace.”

Black’s national profile grew with the Kennedy Smith trial. After the acquittal, he appeared on numerous television programs, “clearly enjoying his new national and international fame,” Dunne wrote in Vanity Fair. He eventually married one of the jurors, Lea Haller.

“He infuriated counselors from rape crisis centers around the country by saying in USA Today about Smith, ‘The jury got a look at him. They saw he was articulate, well-spoken, the antithesis of a rapist,’” Dunne wrote, quoting Black.

In fact, Black’s strategy in the key cross-examination of Bowman’s friend Anne Mercer had been to posit the utter unlikeliness that so presentable a young man as Smith could be capable of rape. Bowman had summoned Mercer for help on the night in March 1991 when Bowman said Smith had raped her outside the Kennedy compound in Palm Beach. Mercer said she had encountered Smith there, but Black challenged her account.

“Black decimated her piece-by-piece,” Dunne wrote. “All professional kindliness gone, he moved in on Mercer like a hungry pit bull, in a belittling attack laced with sarcasm.”

Black went on to other triumphs at the bar, notably gaining the acquittal in 1993 of a Miami police officer, William Lozano, who was accused of killing a Black motorcyclist, Clement Lloyd, in 1989, sparking three days of rioting.

Initially convicted, Lozano was granted a new trial in Orlando, Florida, after an appeals court ruled that the first one should not have been held in Miami. Daringly, Black eschewed mounting a defense in the 1993 retrial, reserving his firepower for the closing argument, in which he appealed to jurors’ sympathy for police.

“Every day, robbers, rapists and thieves come into this courtroom and get the benefit of the doubt,” Black said. A policeman “wearing our uniform” is also “entitled to the benefit of the doubt,” he continued.

His career as a celebrity lawyer was cemented by regular appearances on the “Today” show and “Larry King Live.” He eventually hosted his own television show, “The Lawyer” — a “reality show knockoff of ‘The Apprentice,’” Alessandra Stanley wrote in the Times in 2005.

Black represented Bieber in a 2014 drunk-driving case, securing a plea deal for him; Joe Francis, the creator of the adult-entertainment video franchise “Girls Gone Wild,” in a case involving tax evasion, in which Francis also accepted a plea deal; and Limbaugh, the conservative radio host, when the Palm Beach County prosecutor in 2003 began looking into whether Limbaugh had used prescription drugs illegally. In another agreement that avoided serious penalties, Limbaugh accepted a single charge of prescription fraud that would be dropped if he continued treatment.

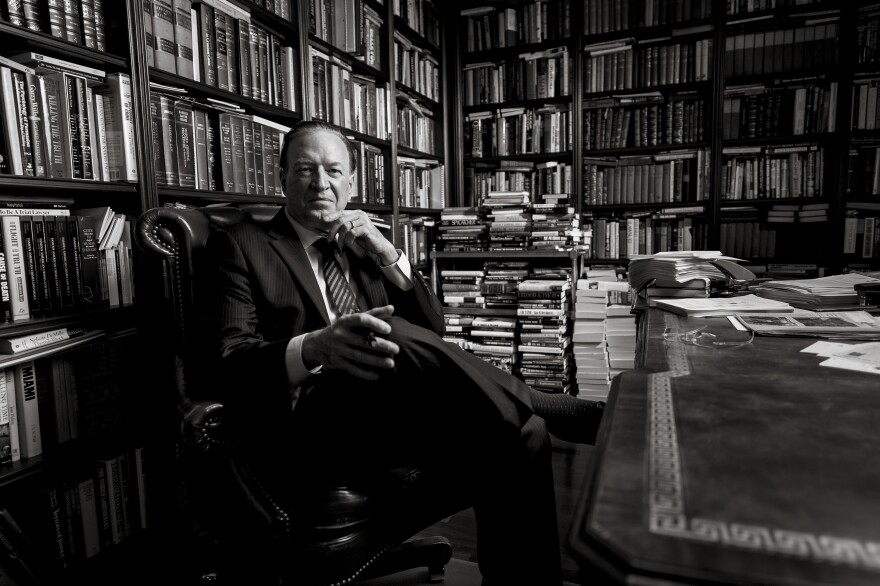

His colleagues in the Miami bar called Black “the Professor” for his intellectual demeanor and his love of reading. Black told Miami magazine in 1998: “The great trials of the century are always dealing with something beyond the facts of the case. They deal with social issues or social trends that resonate with people.”

He is survived by his wife; a daughter, Nora; and a son, Roy Jr.

This article originally appeared in The New York Times. © 2025 The New York Times