On weekday mornings in Liberty City, the City of Miami Trolley is a vital service, transporting seniors with carts, children in school uniforms, and workers transferring to Metrorail or Metrobus. But when Saturday arrives, the green and orange buses vanish.

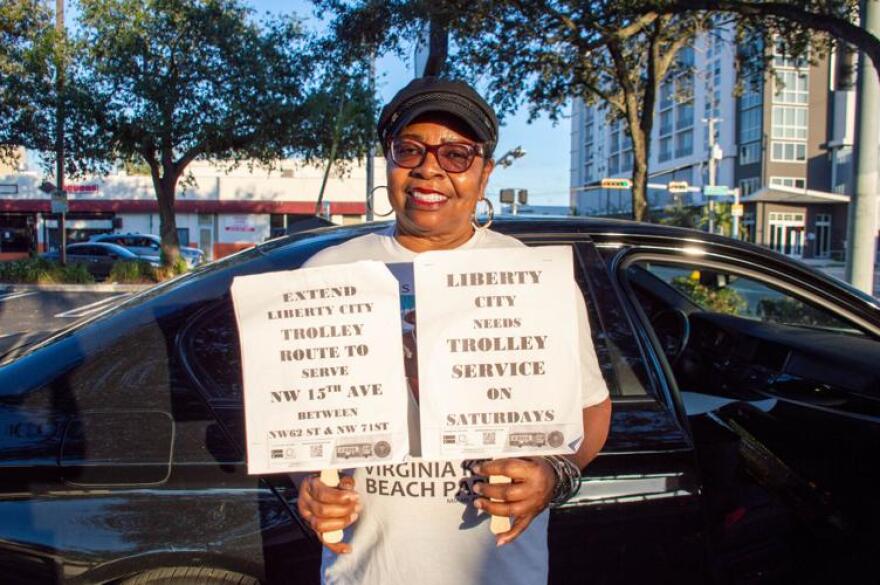

“I use the trolley every day. It’s the best thing they could have come up with, except we need it on Saturdays,” said longtime Liberty City resident Mary Williams. “I catch the trolley so I can go to the Publix Supermarket or Ross in Downtown, also to go to Winn Dixie, which is very important because a lot of people like myself don’t have transportation.”

Liberty City, a historically Black neighborhood, is one of only two trolley service areas in the City of Miami, along with Overtown, that lack Saturday service.

“We need a trolley on Saturday. It’s a necessity. It’s not a luxury,” emphasized resident and advocate Mary Washington.

Ridership is up, but still no trolley

The Miami Trolley Management program is run by the City of Miami’s Department of Resilience and Public Works’ transportation unit. The system includes 13 routes stretching across about 112 miles.

Liberty City's trolley launched late, in 2019, despite the program having started in early 2012. The route uses just two trolleys, looping from the Allapattah Metrorail Station along Northwest 62nd Street and Northwest 7th Avenue before connecting to other trolleys and buses. For years, community advocates have pushed for more responsive routing, clearer signage, and Saturday service.

Washington began digging into the issue in 2021 after hearing that the city was considering cutting Liberty City’s trolley service due to low ridership.

“When I looked online at the trolley map for Liberty City and Overtown, in my opinion, it looked like a fifth-grade drawing,” Washington recalled, comparing it to other maps.

She also discovered missing stop signs, which contributed to the perceived low ridership.

“People don’t know to ride the trolley because they don’t know that’s a trolley stop,” she said.

After repeated requests from advocates, the city installed temporary — and later, permanent — signs and redesigned the map. Washington said ridership subsequently increased by 10,000.

According to data shared with Washington by the transportation department, Liberty City's ridership is now higher than in some service areas that already have Saturday trolleys.

READ MORE: Coral Gables to launch free southern loop trolley pilot

In FY 2023–2024, the Health District recorded 40,822 riders, Coconut Grove had 83,796, and Liberty City had 90,291. In FY 2024–2025, as of May 2025, the pattern continued: the Health District reported 29,072 riders, Coconut Grove 61,050, and Liberty City 64,771.

Overtown, which also lacks weekend service, has seen ridership tick up as well, from 22,985 rides in 2023–2024 to 23,193 by May 2025.

Despite the clear data, Washington says her requests for Saturday service are met with the same answer: the city needs to “look at the master plan” or hold a citizen focus group, a conversation she says has been ongoing for months without resolution.

“The people who ride the trolley are not people who can get to a place where you’re gonna have a citizens focus group,” Washington said. “Those people have to go to work; they can’t just go out to a focus group.

The Miami Times contacted the City of Miami’s Department of Resilience and Public Works several times but did not receive a response by the time of this publication.

Barriers to services and health

For many, the trolley is a connection to life's necessities. Annie McGregor relies on it to get to the Carrie P. Meek Senior Center, doctor appointments, and Winn-Dixie. When the weekend arrives, she struggles.

“I have two daughters, but they work. You can’t bother them all the time,” she explains, noting that without the trolley, she is often stuck at home.

Washington said she has met seniors who are afraid to cross wide, dangerous streets and instead rely on the trolley to get to nearby grocery stores.

“There are some seniors who live in the senior buildings; they will get on the trolley at 7th Avenue and 62nd Street. They will ride that trolley all the way down to the Allapattah Metrorail station and come back around and get over to El Presidente (621 N.W. 62nd St.).”

The weekend service gap is also considered a public health issue. Berlinda Dixon, a complex-case manager with Dade County Street Response and the Doctors Within Borders’ free clinic, described the trolley as serving an essential role for her patients. The clinic, located at New Covenant Presbyterian Church, offers free medical care, hot meals, and groceries from the "Village (FREE)DGE." The clinic is open Thursdays through Saturdays, the one day with no trolley service.

"If you have to come get groceries on Saturday at the food pantry, there’s no trolley for you to take," Dixon said. "We’re talking about people who only have a certain amount of income.”

Beyond medical access, Dixon noted, the trolley doubles as a cooling station amid extreme heat and a temporary shelter during cold snaps for the unhoused community.

“People will ride the trolley to seek shelter and have air conditioning and to take a nap,” she said.

For a neighborhood with a median household income of around $40,964, the cost difference between a free trolley and other public transit options is a heavy burden. A $5 round-trip bus fare — or even more, for connecting routes — every Saturday can be financially crippling.

“You’re out there and waiting for the bus for about an hour or something, and then you have to catch more than one bus,” Williams explained. “Like myself, I would have to catch two buses to get to Winn-Dixie, when I can catch a trolley and get one route for free.”

Equity concerns and solutions

Advocates feel their community is being disrespected and overlooked. The disparity is blatant when comparing Liberty City to tourist-heavy areas.

“You can go to the casino on Saturdays because there are lots of trolleys that go to the casino. There are lots of trolleys that treat our tourists, but what about the residents? These people need free transportation just to go about their daily lives,” Washington said.

A Liberty City trolley stop at Northwest 62nd Street and Northwest Seventh Avenue.

Dixon didn’t mince words.

“It’s definitely a blatant discrimination, putting the low-income population at a higher risk of lacking the services and not being able to get to the services they need.”

The route also suffers from poor infrastructure and maintenance. Nancy Dawkins, a retired educator and Liberty City leader, described how broken lifts prevented elders and disabled riders from boarding, forcing them to wait hours for the next trolley. Washington recalled a time when she says a dead dog was left on a trolley bench near a school for weeks, suggesting a lack of city accountability.

Washington says she has observed other service areas running four or five trolleys on Saturdays, while Liberty City has none. She suggests reallocating a couple of those trolleys for a modified Saturday route.

“No one has told me why we can't get a trolley on Saturday in Liberty City,” Washington said, “even though our ridership numbers are higher than the Health District, which has a trolley. Liberty City can't get one, and no one has told me why.”

She has sent city staff her suggested Saturday routes and schedules, designed specifically around community needs — stopping at grocery stores, Liberty Square’s new businesses, clinics, and senior centers — but has yet to receive a substantive response.

Washington's core message to officials is simple:

“Do you know how much money the people in this 33127 ZIP code make? Do you know how much money they make in the ZIP code where you got five trolleys? The trolley is free, $2.50 for the bus, $3.50 for STS (Special Transportation Service). We make the free trolley. That in itself is dropping the mic.”

This story was produced by The Miami Times, one of the oldest Black-owned newspapers in the country, as part of a content sharing partnership with the WLRN newsroom. Read more at miamitimesonline.com.